New York City is rolling out a $16.5 million initiative to recruit and retain nonwhite male teachers so that its teaching staff better reflects its student population.

The effort, led by the city’s Young Men’s Initiative, a group comprising dozens of local programs serving young black and Latino men, aims to add a total of 1,000 black, Latino and Asian men to New York City classrooms or into a teaching track by the fall of 2017.

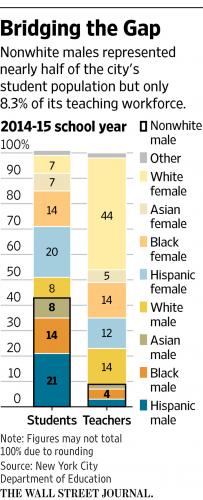

According to data from the city’s Department of Education, Black, Latino and Asian male students comprise 43% of the one million students in the city’s public prekindergarten, elementary, middle and high schools. But men of the same races make up 8.3% of the approximately 76,000 teachers at those schools.

“Our teaching force does not look like the students in the classroom,” said Richard Buery, deputy mayor for strategic policy initiatives. “The city’s workforce should look like the city.”

The money behind the initiative is going toward professional development, advertising, guidance counselors and support for people getting teacher certification. The hiring effort is also intended to break a backward slide.

Most of the nonwhite men currently working as teachers have been employed by the city for 10 to 20 years, according to W. Cyrus Garrett, director of the Young Men’s Initiative, and some are nearing retirement age. At the same time, 8% of new hires, regardless of race or gender, quit in their first few years of teaching.

The city loses 450 to 500 nonwhite male teachers a year, Mr. Garrett said, and hires about 350.

Mr. Garrett and Mr. Buery said there was poor recruitment and retention of male teachers of color and cited several factors that they see as contributing to the problem.

Many such teachers are thrust into roles as school disciplinarians, called in frequently to de-escalate situations between students, Mr. Buery said. He described the phenomenon as the “ Joe Clark problem,” referring to the legendary baseball-bat-wielding principal of a school in Paterson, N.J., and the subject of the 1989 film “Lean On Me.”

At the same time, these teachers are often the ones whom male students of color seek out for mentorship and support, as well as to serve as spokesmen or advocates, according to Amy Wells, a professor of sociology and education at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

Often male teachers of color “feel like they have to defend a lot of students against implicit biases or microaggressions,” said Ms. Wells. “If you’re the only teacher of color on a predominantly white faculty, that can get exhausting, especially when you’re working in an environment where most of your colleagues don’t necessarily understand what you’re saying.”

Often male teachers of color “feel like they have to defend a lot of students against implicit biases or microaggressions,” said Ms. Wells. “If you’re the only teacher of color on a predominantly white faculty, that can get exhausting, especially when you’re working in an environment where most of your colleagues don’t necessarily understand what you’re saying.”

Timothy Chen, a second-year computer-science teacher at Urban Assembly Gateway School for Technology in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood, doesn’t remember having a single teacher of Chinese descent in his hometown of Chelmsford, Mass., but he is one of three at his current school. He has heard from other teachers that some male students look up to him as a role model, he said, and relate to him by talking about videogames.

At the same time, “students can say some culturally insensitive things, both intentionally and innocently,” he said. “The conversation you have with the student following that had potential to be a very powerful learning moment.”

Experts say diversifying teaching ranks has been a perennial problem, dating back to desegregation. School districts have employed a variety of means, including financial incentives, to entice people into the profession.

In New York City, the new cohort of teachers will be primarily drawn from the City University of New York. The city estimates that teachers employed through the NYC Teaching Fellows and Teach for America programs will fill about 400 slots.

The CUNY recruitment plan focuses on increasing the pool of aspiring teachers by both identifying early candidates for a teaching degree and helping established students graduate on time and get all their credentials. This winter, for example, CUNY will add nine guidance counselors to help would-be teachers complete their training.

Principals, too, will be part of the effort by helping to ensure that teachers are placed in jobs and by providing mentors for them. Some type of summer employment, such as working at a summer camp, will also be offered to teachers to help get them past a three-month gap between a hiring date and the start of the school year.