David Thies was one of those kids who played school at home.

“I’d rope in my grandmother and sister to be my students,” he said.

By middle school, he knew he wanted to be a teacher and work with elementary school children. What he did not realize right away was how unusual that would make him.

“People would tell me elementary schools needed more male teachers, and I would be in demand,” he said. “They were right.”

Thies, who is this year’s Cumberland County teacher of the year, was hired right out of college and is now in his 13th year in the Vineland School District, where he teaches fifth grade at D’Ippolito Elementary School.

Male teachers made up just 24 percent of all certified teachers working in New Jersey public schools in 2009-10, state Department of Education statistics show. That percentage has remained constant during the past decade even as the number of teachers has increased. In 1999-2000, 23,750 men were among the state’s 94,415 teachers. Last year, men made up 27,063 of 114,705 teachers working in public schools.

Bryan Nelson hopes that trend is shifting a bit. The founder of MenTeach said there was a slight increase in male teachers nationally last year, likely related to the recession and a shortage of other jobs. He said the last increases in male teachers were in 1929 during the Great Depression and in 1944, when the G.I. Bill gave more men the opportunity to attend college.

He said men face three major roadblocks to becoming teachers: the stereotyping of teaching as a feminine profession, especially in lower grades; a fear of pedophiles preying on children; and the relatively low status and pay.

“It’s just still considered a more feminine culture, and that takes a long time to change,” Nelson said.

Most male teachers are in high schools. State data do not break down teacher assignments by grade, but the percentage of male teachers in regional high school and vocational school districts, where as many as 40 percent of teachers are men, far exceeds the percentage in kindergarten through eighth-grade districts, where as few as 10 percent may be men.

Role models for life

School officials say the issue is not whether one gender is better at teaching but that schools should represent life. When the men most children see in a school are custodians, security guards or gym teachers, they do not get a complete picture of the roles adults play. In urban schools, where many children are being raised by single mothers, male role models help teach boys how to become responsible men.

“First you look for quality educators,” said James Knox Jr., principal of the New York Avenue School in Atlantic City, and a former elementary school teacher in the district. “But it doesn’t hurt to also have good, strong males. Schools should mirror the world.”

Knox has about 15 male teachers at his pre-kindergarten to eighth-grade school. He said the mix provides a balance that is crucial to the atmosphere of the school. He recalled as a teacher being sent “problem” students who needed a male role model, and his male teachers know that is part of their job. They see it as no different than parenting.

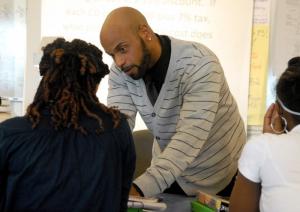

“I approach all kids as if they were my own,” said Dawud Akram, who teachers seventh-grade math at the New York Avenue School. “You do need to have patience, and most men I know don’t.”

For the male teachers interviewed, teaching is a calling. Some gave up more lucrative jobs in private industry to become teachers.

“You have to go into it accepting that you’ll never make a six-digit salary, unless you go into administration,” said Jerome Taylor, who has taught for 15 years. “It’s frustrating to me to see male teachers working two jobs to support a family.”

John Levai, a veteran music teacher at Maud Abrams Elementary School in Lower Township, Cape May County, left a job managing a paint store and took a $7,000-a-year pay cut to become a teacher.

John Levai, a veteran music teacher at Maud Abrams Elementary School in Lower Township, Cape May County, left a job managing a paint store and took a $7,000-a-year pay cut to become a teacher.

“I look forward to my job every day,” he said. “And I see the importance of male role models in elementary school, even if I’m now more of a grandfather figure.”

Matt Reidenbach, a third-grade teacher at Maud Abrams, was in the family pest control business and realized his favorite part of the job was training people. Now in his 14th year teaching, he sees his job as playing an integral role in his community.

“I took a huge pay cut to come here,” he said. “But it was the best move. When you do a great lesson, you can see the response. It makes your day.”

Teaching styles

The male teachers admit to being partial to certain age groups. The men at Maud Abrams love that the third- and fourth-graders are mature enough to handle more challenging lessons, but still young enough to act excited and silly. The middle school teachers like guiding adolescents through raging hormones into high school.

“I’m doing what I’d want someone to do for my child,” Taylor said. “It does go beyond the curriculum.”

Barbara Dalrymple, principal at Maud Abrams, said she feels lucky to have several men in the school because they bring a different perspective. She said at first there was the occasional parent concerned about their child having a male teacher, but they are now well-known enough that it’s not much of an issue.

But the male teachers know the concern still exists.

Kevin Coombs, a special education/social studies teacher at Maud Abrams, said he was offered a job in a preschool handicapped program but was concerned that changing diapers and having close physical contact with 3- and 4-year-olds might be misinterpreted.

Dalrymple said male teachers are tuned in to what boys like and can help get boys excited about school. She cited a meeting during which teachers shared techniques for encouraging boys to read. Several have a bulletin board of a football field. Students advance yards by reading books and getting good test scores. Everyone who scores a touchdown is invited to a Super Bowl party. In the spring they switch to baseball diamonds and race cars.

“We need to encourage all children to read, but particularly our young men,” she said.

Some students said they like having a male teacher, while others are not so sure. Still, most of their comments could be made about any teacher.

“He is a strict, orderly person,” student Khalei Gaines-Kelly, 10, said of Thies, who also was accused of giving a lot of homework.

“He’s hilarious,” said Richard Cervini, 10.

Some students who had never had a male teacher before were a bit intimidated, at least at first. But some parents have even requested a male teacher.

Some students who had never had a male teacher before were a bit intimidated, at least at first. But some parents have even requested a male teacher.

“You try to match the students with the teacher,” said D’Ippolito School Principal Gail Curcio, who has male teachers in kindergarten, second, fourth and fifth grades. “Some students need more structure. Some need motherly nurturing. You want to have options. But it is different when students have a male teacher. It’s not just another mom.”

Recruiting more men

Teachers interviewed said the best recruitment tool may be just having more men in the school so they do not seem so unusual. But as more women take on administrative roles, men have even fewer role models to encourage them. In 1999-2000, men held 58 percent of administrative jobs. By 2009-10, that dropped to 48 percent.

Jonathan Lelli, a special education teacher at the New York Avenue School for three years, said the more experienced teachers were role models for him when he started.

“It did feel good to have male teachers to talk to when I came here,” he said.

The Future Educators Association works nationally to recruit more teachers, especially in math and science fields. Director Jeanne Storm said they try especially to recruit from under-represented groups, and that includes men. The association runs the Center for Future Educators at The College of New Jersey.

Mark Chando has been teaching science for 20 years in Atlantic City, mostly to middle school students.

“Just being here can help,” he said. “I had a sixth-grader ask me this year how many years he would have to go to school to become a science teacher. The kids know if you care or not. If you do, you can make a difference.”