Arnold Blume: Substitute Teacher Tells History First Hand

The substitute teacher in Room 216 was pacing, searching for the right touchstone to help an eighth-grade social studies class in this mostly white, affluent community comprehend the sting of racial discrimination.

“O.K., have any of you ever seen the TV show ‘All in the Family?’ ” he asked.

Some of the Abercrombie-clad 12- and 13-year-olds looked up from their dog-eared three-ring binders. Some studied their cuticles. One girl tentatively raised her hand.

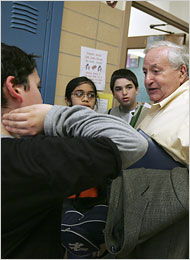

Arnold Blume, 81, their teacher for the hour, dressed in pressed gray slacks, a pinstriped button-down shirt and a midnight blue blazer, scanned 20 faces like a captain searching the open sea for a speck of land. He dropped Archie Bunker and tried another tack.

“Does anyone know what a restrictive covenant is?”

No takers. Finally, Mr. Blume and his temporary wards found common footing on a patch of narrative ground where every human, it seems, can stand: “Let me tell you a story about when I was young,” he said, and every young face turned to listen. It is Mr. Blume’s trademark.

On any given day in the United States, about 274,000 people report for work as substitute teachers. Mr. Blume, who retired in 1983 after 29 years teaching English and social studies and has generally substituted four days a week at Great Neck North Middle School for the past two decades, may or may not be the oldest.

But it is safe to say there are not too many people who have taken attendance, led the Pledge of Allegiance, spoken the words “boys and girls,” handed out a bathroom pass or asked for undivided attention and gotten it as often as he has.

He is no beleaguered sub from Central Casting. He has never had to call security. He does not even have to write his name on the blackboard. Everyone knows Mr. Blume.

In a school where the average age of the teachers is under 40, and the students’ grandparents include many of the baby-boomer cohort, Mr. Blume has emerged as a sort of older person in residence, an on-call doctor of memory.

He is the only person in the building, for instance, who remembers the shantytown Hooverville that once blanketed Riverside Park at 72nd Street. He talked about it the other day in Miss Mostrande’s eighth-grade social studies class.

He is the only one who had ever heard of, much less laid eyes on, a sign that said “No Jews, No Negroes, No Dogs Allowed.” He explained how that felt on another day in Ms. Andersen’s eighth-grade English class.

He is the only person whom Lena Ferreira, a 13-year-old eighth grader, ever met who can tell you what it was like listening to the radio with his mother the day Franklin Delano Roosevelt made that inaugural speech in which he said, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

“He made me love social studies,” said Angelique Dedvukovic, 13. “A lot of kids don’t know how life used to be harder. He tells you about how it wasn’t always like this. Because he lived through it.”

Barbara W. Andrews, North Middle’s principal, said Mr. Blume had carved out a niche at the intersection of teaching and oral history. He may not follow lesson plans as much as some would hope, and he has been known to talk a little too much about himself, she said. “But Arnie brings something to our school that no one else brings,” she said. “He gives the kids a sense of the reality of the past.”

Barbara W. Andrews, North Middle’s principal, said Mr. Blume had carved out a niche at the intersection of teaching and oral history. He may not follow lesson plans as much as some would hope, and he has been known to talk a little too much about himself, she said. “But Arnie brings something to our school that no one else brings,” she said. “He gives the kids a sense of the reality of the past.”

In an eighth-grade English class studying “A Raisin in the Sun,” Mr. Blume talked about a trip to Miami Beach in 1941, when the police knocked at the door in the middle of the night and ordered his family housekeeper, a black woman, to leave the all-white hotel. (His whole family left.)

In seventh-grade Spanish, Mr. Blume moved seamlessly from a confession that he cannot speak Spanish to a tale of the European sabbatical he took in the 1960s with his wife and two children, then 9 and 6, where they visited Spain and learned to love the siesta.

And in a seventh-grade science class, where the lesson called for a review of DNA facts, Mr. Blume reviewed some DNA facts. Then he told the story of searching for the family of his biological father, Wolf Garfinkel, who left when Mr. Blume was 6. (He took his stepfather’s name.)

Walking between classes, he received shout-outs in the hall: “Hey, Mr. Blume! Are you coming to my class today? Hey, Mr. Blume! Will you tell us a story today?”

Moments later, a girl with braces and long, unruly hair stopped Mr. Blume to report – her every sentence ending with a profound question mark – “The most amazing thing happened, Mr. Blume. My mom bought a box of chocolate cookies. And I ate them all. And then at Hebrew school, they had some other cookies. And I ate some. And I was so hyper I couldn’t sleep last night! And I’m still kind of hyper!”

Mr. Blume held his small briefcase close to his chest. “I see,” he said. Even Mr. Blume sometimes does not know what to say.

Geoffrey G. Smith, director of the Substitute Teaching Institute, a training organization supported by the Utah State University College of Education, said about 10 percent of the nation’s substitutes were retired teachers like Mr. Blume. Mr. Smith said there had been no studies on how many substitutes were over 80, but he suspected it was a small number.

Asked what makes a good substitute, Mr. Smith recited a list of dos and don’ts that included dressing neatly, having a positive attitude and avoiding sitting down in front of the children, summarizing the ethos as being “someone who uses the time allotted to teach” rather than baby-sit.

In the course of a couple of days at North Middle, weaving his narrative through classes in English, Spanish, math, science and library research (“I’ll do anything but gym”), Mr. Blume taught a cross-section of the school’s 600 students many interesting and amazing things.

He told them that he had never heard of the SATs in his day; that unlike people in New York, people politely line up for taxis in London; that ancient Rome was ruled by an “oligarchy” (“o-l-i-g…” he scribbled on the board); that the Spanish lost the Battle of Santiago in 1898 by allowing American ships to carry out a maneuver called “crossing the T”; that once upon a time medical doctors went to people’s homes; that the trenches dug during World War I were usually about eight feet wide; that after World War II, quotas limiting the admission of Jews and Roman Catholics were still being enforced by many colleges.

Whatever the curriculum, the outlines of his life story emerge: Father left. Raised in boarding houses. Mother remarried. Army Air Corps in World War II. Marriage. Two children. Divorce. Remarriage.

The generational divide between a man in his 80s and a child of 12 or 13 may be about as wide as the brain can bridge, but there seemed at times a gamelike quality to the effort.

“Uh, the show where they sing …” Mr. Blume said at one point, stuck.

“American Idol!” yelled the pupils.

Or: “Those cards they bought food with?” asked a student.

“Ration cards,” said Mr. Blume.

Sometimes, Mr. Blume is given less than optimal assignments, like detention. Sometimes, despite his best effort, he faces a sea of blank stares, of split-end studying, of furtive text messaging.

But for a teacher without a subject or a homeroom or a grade book of his own, Mr. Blume has forged his share of what teachers like to call teachable moments during his 20 years as a sub. Most seem to start with, “Did I ever tell you this story?”

He told the one about the day Roosevelt died to Mrs. Bronheim’s eighth-grade social studies one recent afternoon. The class was studying the Great Depression. That day in 1945, Mr. Blume was a 19-year-old soldier in the Army Air Corps, stationed in Florida. The troops assembled for a memorial march.

“Twenty-five thousand of us” in dress uniforms, he said. “We were all 19 and 20 years old. He was the only president any of us had ever known. I was crying like a baby, and so were a lot of the others.”

At that point, the students looked up from their cuticles and their end-of-day adolescent imperviousness. The room was silent. And Mr. Blume told his story.