Many media sources have propagated the view that black male teachers are “becoming extinct.” Currently, black males represent less than 2 percent of the nation’s teacher workforce. One article suggests that black males are underrepresented in the teaching profession because they prefer to pursue more lucrative careers. The article also postulated that because black males have had negative educational experiences, they are less likely to choose a career in education.

What are the consequences of black males evading a tacit moral obligation to teach? Several years ago, CNN suggested that placing black men in the classroom could be the answer to solving problems in the black community such as gang violence, high school dropout rates and fatherless homes. According to most reports, the lack of black male teachers results in abysmal deficiencies in the educational progress of black male students.

Unfortunately, this narrative on black male teachers is based on supposition and stereotyping, not a careful analysis of the data. Males of all races are underrepresented in the U.S. teaching force. The percentage of white male students in pre-K through 12th grade is twice the percentage of white male teachers; the percentage of black male students is more than three times the percentage of black male teachers; and the percentage of Hispanic male students is almost seven times the percentage of Hispanic male teachers. Asian males represent less than 0.5 percent of the teaching force.

Later this month, Chance Lewis and I will release a book titled “Black Male Teachers: Diversifying the United States’ Teacher Workforce”. In the book, we suggest responsible methods of increasing the number and capacity of black male teachers, without subjecting them to differential standards of success. For this entry of Show Me the Numbers, I examine the myths used to explain the shortage of black male teachers, and why the purpose of diversifying the nation’s teacher workforce should be to benefit the teaching profession, not individual students.

Black males are not avoiding the teaching profession because they are less altruistic and more interested in lucrative careers.

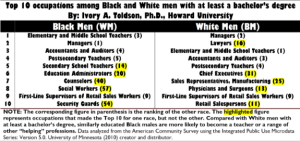

Recently I conducted an analysis of the top 10 occupations among black and white males who have at least a bachelor’s degree (see table). Primary school teacher was the No. 1 profession of college-educated black men and No. 3 for white men. Secondary school teacher was No. 5 for black men and No. 14 for white men. Educational administrator was No. 6 for black men and No. 20 for white men, and counselor was No. 7 for black men and No. 40 for white men.

The occupations that were in the top 10 for college-educated white men but not for college-educated black men were lawyer, chief executive, sales representative and physician and surgeon. Overall, higher-paying occupations are more commonly held among white men, even when controlling for education. Black men who are college-educated are far more likely to be a teacher or in a range of other “helping professions.”

Reasons for the shortage of black male teachers are diverse and nuanced.

Several reasons account for the dearth of black male teachers. First, black males are only 5.5 percent of the adult population, and 16 percent have completed college. Second, black males are less likely to major in education. In 2009, 7,603 black males and 25,725 black females graduated from college with a degree in education.

Interestingly, an upward-mobility advantage within the field of education also appears to reduce the number of black men in the classroom. Almost 7 percent of black males with a degree in education become educational administrators, compared with 5 percent for black females and white males, and only 2.8 percent for white females.

If current trends in occupational choice stay the same, as more black men enroll in and graduate from college, that will naturally increase the number and percentage of black male teachers, with complementary increases in black male physicians, lawyers, engineers, nurses, bankers, brokers and other professions.

No evidence suggests that increasing the number of black male teachers will eliminate the achievement gap.

Black male teachers are well-represented in Memphis, Tenn., where they represent 6.5 percent of the teaching force — more than three times the national average of 1.8 percent. They are scarce in Tallahassee, Fla., where they represent less than 1 percent of the teaching force. Montgomery, Ala., has the highest percentage of black male teachers. In this city with a population of 206,297 (71 percent black), more than 1 in 4 (26 percent) of the teachers are black males. However, most Southern cities are more similar to Baton Rouge, La., which has a population of 439,013 (52 percent black), and less than 1 percent of the teachers are black males.

According to “The Urgency of Now: The Schott 50 State Report on Public Education and Black Males,” from the Schott Foundation for Public Education, the graduation rate for black males in Baton Rouge is 42 percent, and the graduation rate for black males in Montgomery is 33 percent. Notably, graduation rates for white males in both of these cities are less than the national average for black males.

In the 10 metro areas with the largest number of black people — New York City, Chicago, Atlanta, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles-Long Beach, Dallas-Fort Worth and Baltimore — Baltimore has the highest percentage of black male teachers, with 5.4 percent. Los Angeles and Detroit have the lowest, with 2.3 percent. Notably, all of the large metro areas with a large black population had a percentage of black male teachers that was higher than the national average.

When one connects the cities to corresponding graduation rates as presented in the Schott report, there is no compelling evidence that the presence of black male teachers alone will improve graduation rates for black males. However, keeping this information within its proper perspective, even in a district with a representation of black male teachers that is consistent with the representation of black men in the U.S. population, black male students would have little interaction with black male teachers. A black male student, who has had about 55 teachers from kindergarten to 12th grade across all subjects, could expect to have had one black male teacher in Detroit and three black male teachers in Memphis.

The systemic benefits of black male teachers can be realized only through their relationship to the teaching profession, not through their relationship with individual students.

The U.S. needs a teaching force that is drastically more diverse to represent the current demographics of the pre-K-through-12th-grade student population. The disproportionate number of black students who are suspended, are placed in special education and do not graduate with their cohort suggests problems related to equity and inclusion in U.S. educational systems. Diversifying the teaching force could address underachievement among black students; however, the solution will not be realized through race matching of teachers and students.

Recently, after an edict from U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, the media began to romanticize the idea of having more black male teachers. We understand that role models are important, and black male teachers are in a strategic position to interact with black male students five days a week. However, recent media coverage of the lack of black male teachers has led to many misconceptions and misguided policies.

We miss the opportunity to harness black males’ natural affinity for the teaching profession by promulgating the misconception that black males are uninterested in teaching. Selection biases within alternative teacher-certification programs, such as Teach for America, and well-documented deficiencies with national teacher-certification examinations thwart many black males’ ambitions to teach.

Also, educational administrators should enforce the policy that every teacher, regardless of race or gender, is prepared to teach any student. White female teachers especially, as the profession’s majority, should gain the tools of cultural competence to serve any student regardless of racial background or gender.

Increasing the number of black male teachers is important, but as a minority in the teaching profession, they should not become props for shortcomings in the educational system. Beyond incidental connections with individual students, black male teachers can serve as models and mentors to novice teachers of all races.

The presence of black male teachers at a school can help other teachers realize the potential of their black male students and clarify any misconceptions these teachers may have about the black community. Black male teachers can conduct workshops and help review training proposals for cultural relevance.

In short, it is prudent policy to promote diversity in the teaching force, but irresponsible practice to assign students to instructors based on race. Black male teachers need to be properly trained to meet the needs of all students, and all teachers need to be properly trained to teach black students.

Ivory A. Toldson, Ph.D., is a tenured associate professor at Howard University, senior research analyst for the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, editor-in-chief of the Journal of Negro Education and contributing education editor at The Root. He can be contacted at itoldson@howard.edu.