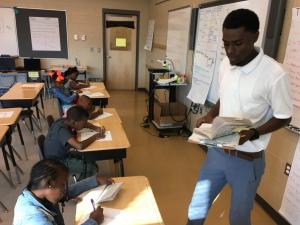

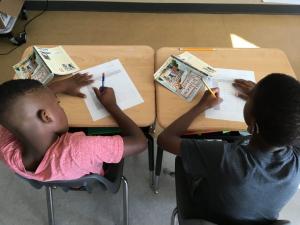

Yawns and sleepy stretches punctuated the silence as Brandon Mercadel’s third-graders rooted around their desks for “The Buried Bones Mystery,” the subject of today’s lesson about text evidence.

“You guys must have had an amazing Father’s Day weekend,” said Mercadel, smiling. “You are so tired!”

One student laid his head on his desk and slipped off his high-top sneakers, prompting another student to silently mouth “pew!” and clamp his fingers to his nose.

Mercadel smoothly switched tracks and lead the group of seven children in a rousing set of full-body stretches and jumping jacks.

“Okay, let’s try this again,” he resumed, his students back in their seats, books in hand. “Therese, it’s your turn to read. Remember: loud and proud.”

Mercadel is 22 and will be a senior at Xavier University of Louisiana this fall. This is his second summer teaching a six-week intensive camp called Summer Experience, a collaboration between Relay Graduate School of Education and New Orleans-based charter network, FirstLine Schools. Mercadel earns $2,250 for his work as a summer teaching fellow. In addition to providing a free, semi-academic camp for local children who attend FirstLine schools, the goal of the program, say its organizers, is to hook college students like Mercadel into a long and stable career in teaching.

It’s one effort to help avert a brewing crisis for New Orleans schools: By 2020, the city will need to hire more than 900 teachers annually, an increase of nearly 40 percent from 2010, according to estimates by New Schools for New Orleans. To fill those slots, many schools are looking for teachers like  Mercadel: a black, male, New Orleans native, with plenty of family living in the city, who is deeply committed to the teaching profession. Research shows that black teachers connect more deeply, hold higher expectations, and provide stronger role models for black children, who make up nearly 90 percent of the city’s public school students. The hope is that teachers with family roots in the city will stick around, slowing down the rate of teacher departures, which doubled after post-Hurricane Katrina reforms.

Mercadel: a black, male, New Orleans native, with plenty of family living in the city, who is deeply committed to the teaching profession. Research shows that black teachers connect more deeply, hold higher expectations, and provide stronger role models for black children, who make up nearly 90 percent of the city’s public school students. The hope is that teachers with family roots in the city will stick around, slowing down the rate of teacher departures, which doubled after post-Hurricane Katrina reforms.

FirstLine and Relay’s partnership is one of a smattering of efforts meant to address a problem largely of the city’s own making. After Katrina, the entire teaching force, which had been majority black, was fired and had to reapply for jobs. In a push to raise test scores and other metrics, such as high school graduation rates, the state of Louisiana took over most of the city’s schools and converted them to publicly funded, privately run charter schools. Although a small fraction of the fired teachers found jobs in the new regime post-Katrina, schools staffed-up quickly with inexperienced teachers — most of them white — from national prep programs like Teach for America and TNTP’s teachNOLA. Now, the city’s teaching force is 49 percent black; before the storm, it was 72 percent black.

The fixes to the looming staffing crisis that resulted from those policy choices won’t be easy or quick, experts say. “Building talent pipelines that meet the demand for effective teachers and principals is arguably New Orleans’ most pressing citywide challenge in coming years,” wrote researchers in a 2015 report about the state of New Orleans public schools. Yet, the study noted, “There is no easy path to sustaining a great educator workforce that is representative of New Orleans as a whole.”

Consensus about fixing teacher supply and diversity is only a recent development in New Orleans. “There’s the realization now that our schools are adequate but they’re not great. That’s how the reformers put it. Those skeptical of the reforms would probably use harsher language,” said Douglas Harris, professor of economics at Tulane University, and director of the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans. “So the question is: How do you get from good to great? They’re starting to believe that a big part of this is about needing teachers who will stick around.”

Mercadel was 10 years old when Katrina hit the city. “For some of my students, I’m the first black teacher they’ve ever had,” he said. “As a child, most of my teachers were white. But I would mostly connect to my teachers who were black because they understood where I come from culturally, they could relate, and that made a big difference for me. When you’ve only seen one race [as your teachers] for so long, you just think: ‘Where are my own people at? Why aren’t they in the classroom teaching and helping us out?'”

Several additional factors conspired in recent years to reduce the number of qualified teachers. Louisiana slashed its higher education budget, which hurt local university-based education programs. Institutions like the University of New Orleans trimmed or eliminated teacher training programs in an effort to stay afloat, cutting off many of the traditional routes that used to supply local teachers. Negative perceptions of the teaching profession also contributed to the dwindling local teacher supply, an issue that extends far beyond the city limits of New Orleans.

“It’s not that young people are thinking about what path to take to become teachers, it’s whether they should become teachers at all,” said Harris. “Plus, a lot of kids from New Orleans, they would have known teachers and heard about charter schools and how contentious things are.”

Post-Katrina charter school staffing preferences were driven by quality and numbers, said Jay Altman, chief executive officer of FirstLine Schools, which now includes five charter schools in New Orleans. “The national programs, when compared to local programs, were just much stronger. But the challenge — and this isn’t limited to New Orleans — then quickly became about retention,” said Altman. “Also, the numbers of teachers we needed were so big, local programs couldn’t produce enough teachers.”

Mercadel, who juggles a full-time college course load with working four weeknights at Walmart unloading freight from trucks during the school year, originally planned to become a sports physician. “I came from living in poverty, so going into college, I had the mindset that I needed to make a lot of money so I could get out of it,” he said. “I started off as a chemistry pre-med major. Then I realized: ‘You don’t even like science.’ So my second semester, I went over to English education and loved it.”

His first student observation in a third-grade classroom sealed the deal for Mercadel. “I realized that teaching helps me understand who I am as a person: I am a product of New Orleans education,” he said. “Seeing those kids, watching them learn, I realized so much about myself and my own education. That really made me want to become a teacher.”

Tapping into that visceral connection early, and then nurturing and supporting young teacher candidates until they are fully trained to enter — and remain in — the workforce, might be a key to diversifying and expanding the number of candidates who enter the teacher pipeline. At least that’s what organizers of the Relay Summer Experience are betting on as they, along with several other charter management organizations in the city, work on identifying more students like Mercadel and persuading them to try teaching.

“We believe there is a huge population of individuals of color who, early in their career, contemplate going into teaching and, for a number of reasons, they are not pursuing that initial vision,” said Jabali Sawicki, who oversees day-to-day operations at the New Orleans summer camp and is senior director of Inspire for Relay Teacher Pathways. “We see it as our challenge to find ways to diversify the teaching force. And I think one of the best ways to do this is to find those individuals while they’re still open to the idea of potentially teaching, and exposing them to the kind of school experience that is positive, has an impact, and that is joyful. In a lot of ways, that isn’t how people think of school and the teaching profession.”

This summer, 28 undergrads received fellowships to teach Relay’s Summer Experience camp; last summer the group included 18 recipients. Both summers, the program’s young teachers were largely African-American. The six-week program begins with two weeks of intensive teacher training. Teaching fellows then spend one month teaching math, English language arts, and a variety of afternoon enrichment programs such as basketball, poetry, and drama at the summer camp. After campers leave, the teaching fellows round out the day with a professional development session where they learn about, and get to practice, everyday teaching skills such as resetting the classroom, or “teaching with love.”

Not everyone agrees that schools should be focusing efforts on matching students with teachers of the same race. Although recent research bolsters the conclusion that black students in particular have better outcomes when they’re exposed to teachers who look like them, older research hasn’t always backed up those findings.

Sawicki says he’s seen the difference having a teacher of the same race can make, however.

“The individuals who had the biggest impact for me were all African-American males. We want to emulate the people that we respect. To have black males at the highest levels of accountability who articulated their expectations for me, who looked like me, listened to the same kind of music I listened to: it reaffirms our existential belief in ourselves,” Sawicki said. “So, if you’re sitting there, and you’re a black male from New Orleans, and you’re looking at Brandon [Mercadel], and you’re inundated with negative images about black males, and messages about gang violence in New Orleans … you can’t help but look at him and believe there are alternative narratives that can exist for you.”

The Relay program hasn’t yet found the secret to connecting with more local students. This year, the group of teachers-in-training is mostly from Texas, with 12 attending Texas colleges. Only three are originally from Louisiana; six are students in Louisiana colleges who may, or may not, stay in the city post-college.

“We’re not fully there. Yes, we have a high contingent of folks from Texas but that’s also because we have residency programs throughout Texas, so student-fellows are able to go back to their communities and join those residency programs,” said Sawicki. “But long term, the goal is to build deeper relationships with FirstLine and other schools in New Orleans. As we refine our recruitment in cities, wherever Relay has a campus, we would love to have a Summer Experience that partners with that campus and then pull as many local, homegrown folks as possible. But we’re just not there yet.”

At FirstLine Schools, where teacher and student demographics closely mirror those of the rest of the city’s schools, Altman says partnering with Relay’s Summer Experience is just one part of fixing what’s ailing New Orleans’ teacher workforce. “Our goal is to get our teacher demographics much closer to that of the students we serve,” said Altman. He noted that FirstLine is, for example, collaborating along with four New Orleans charter networks in a Xavier University teacher residency in which diversity and community roots are key factors in recruiting candidates. “There are all these pieces to the puzzle of ‘how do we create a range of talent pipelines to create a more representative teaching force?'” said Altman.

For Mercadel, however, the future is crystal clear. “I want to teach for a few years, maybe seven to 10,” he said. “Then I’d like to become a principal. And then move on to the school board. Working my way up to really have an impact on New Orleans education.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.