Dubois County doesn’t have many male elementary school teachers — a reality that is common throughout the country.

According to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data compiled by nonprofit MenTeach, only about 19 percent of elementary teachers in the U.S. were men in 2015, a number that hadn’t grown much more than 2 percent since 2002. Only about 8 percent of teachers are men in Dubois County public elementary schools.

And while the men who teach in area elementaries aren’t exactly sure how to increase that percentage, they do believe they have a unique responsibility to their schools and their students. From being a positive male role model to diversifying instruction styles, the guys know their role in education is important in helping their students grow.

Not counting administrators and maintenance staff, just four men work as teachers at the three Greater Jasper elementary schools, none of whom work at Fifth Street School. Five males have teaching jobs and one has an assistant position at Huntingburg and Holland elementaries. Dubois Elementary has one male teacher, and Celestine Elementary has none. No men teach at Ferdinand Elementary, either, and Pine Ridge Elementary has only one male teacher.

“I think it’s important for kids just to realize that you’re going to have different people, you’re going to have different teachers and different styles,” said Fifth Street School Principal Ryan Erny. “Every boss that you may have is going to be different. It may be a female boss, it may be a male boss. One may be a little stricter (or) laid back, and so for kids to have those kinds of experiences starting now I think is so important for preparing them down the road.”

Before moving into his administrative role at the beginning of the school year, Erny taught fourth grade at Ireland Elementary for 17 years. He said the female teachers he worked with there had no issues disciplining students, but he said they sometimes would ask him to talk to boys and work through problems with them. A few examples that came to his mind were horseplay issues that took place in the boys restroom and disagreements on the playground.

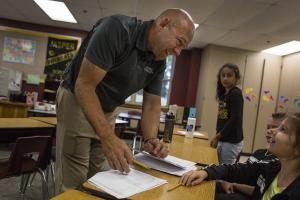

“There’s times where there’s kids that are a little more challenging and have behavior problems that react totally different to males than females,” said Kevin Schipp, a Tenth Street Elementary fifth-grade teacher who has taught at the school for 17 years.

Schipp and Erny don’t pretend they automatically have better relationships or connections with boys because of their gender, but they know they have the power to be difference-makers to kids who don’t have positive male role models in their lives.

“A lot of kids do, but there’s a lot that don’t,” Schipp said. “And I think we have the opportunity to make that impact on them and have that kind of relationship with them.”

The men said students can recognize the disparity between the number of men and women in elementary classrooms, too.

Tenth Street teacher Brock Moeller is in his second year of teaching third grade — a career path he chose in part because he enjoyed having the freedom of blending subjects across the curriculum and not reteaching the same class period after period like he would each day as a middle or high school teacher.

While reflecting on the first two weeks he taught at the school, he remembered how the younger students constantly walked up to him and asked if he really was a teacher.

“One of the kids even said, ‘I didn’t know there were man-people that taught here,’” Moeller said.

The teachers agreed it can be normal for kids who haven’t had a male teacher to be initially apprehensive because the classroom experience is different from what they have had in the past. Some students might be afraid that the men will be stricter than the women, but Tenth Street fourth-grade teacher Wesley Laake said that simply isn’t true.

“There’s a considerable size difference between me and a 9-year-old girl,” Laake said with a laugh. “It may be a little intimidating but … I don’t think Brock and Kevin and I are any more strict than anyone else in the building just because we’re men.”

Parents told Erny in conferences that their children were initially nervous to be in his class, but Erny noted that the anxiety faded almost immediately. And as far as how moms and dads feel about their children being around a man every day, Erny and his peers said parents are typically on board.

“Most parents want their kid to have the other experience of having a male teacher,” Schipp said, echoing Erny.

Schipp, Moeller and Erny couldn’t explain the shortage of male teachers, but they had some theories as to what’s contributing to it. Moeller offered that women have historically taught elementary children, which could result in a stereotyping of elementary teachers that deters men from considering the jobs. Erny speculated that it might be because of the athletic coaching opportunities at the high school level — where about 40 percent of teachers are men — though he coached girls basketball for 17 years at Jasper High School, where Schipp coaches boys track and cross country.

A USA Today story from August suggested that money could be a factor as well. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in May 2016, the median annual wage for elementary school teachers was $55,800. At the same time, the median annual pay for middle school teachers was $56,720 and the median payout for high school teachers was $58,030.

Erny preached the importance of all educators.

“We need good teachers,” Erny said. “Male or female, we just need good teachers that care about kids and want to help and make a difference in lives.”