Each weekday, students filing into Denver’s Ashley Elementary School come face to face with a relatively rare educational experience.

They call it by name: Mr. Johnson. Mr. Heath. Mr. Walters.

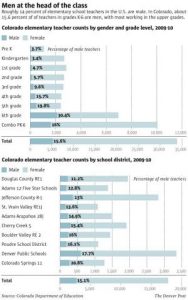

In all, eight of 18 instructors at the K-5 school are men, a proportion that far exceeds the statewide average of 15.6 percent of elementary school teachers — most concentrated in grades five and six.

“Anybody who works with little kids knows they need input from both sexes,” says principal Kenneth Hulslander, who assembled his staff by keeping an eye out for promising male talent among visiting substitutes and student-teachers. “I look at it as being part of the learning experience for my kids.”

Throughout the U.S., men traditionally have shied away from the elementary grades — for reasons ranging from low pay and low status to stereotypes that cast them as less nurturing than their female counterparts and the fear of accusations of inappropriate behavior.

“I think there’s this assumption that there’s a certain maternal quality needed to be an elementary school teacher,” says Peter Vigil, assistant professor of elementary education at Metropolitan State College of Denver. “A lot of men can’t get past the idea that it’s a wiping- noses and herding-cats kind of thing.”

But once in the classroom, do men make a difference?

Some experts note that there’s little data suggesting a definitive correlation between teacher gender and learning. But others contend that men offer the added advantage of providing positive male role models in classrooms teeming with single-parent kids.

North Carolina education consultant Steve Peha zeroes in on the lack of hard data on academic progress tied to teacher gender. And he doesn’t put a lot of stock in the role-model argument, either.

“I want teachers to model interest in reading books, in math, in science, for all the kids,” Peha says. “I’m not too concerned about role, though. I don’t know how much of a difference that’s going to make. I think we should focus on ‘model.’ We know that model works.”

A male or female teacher?

Hulslander, well aware that many of his kids don’t have fathers living at home, weighs several factors in determining where to place students — including whether they’d respond better to a male or female teacher.

He doesn’t aim for percentages but tries to field a teaching staff that reflects his student body — roughly two-thirds Latino, one-third African-American, with a sprinkling of white kids.

“If you’re looking at teaching as this cold, statistical piece of work, then a good teacher is a good teacher,” Hulslander says. “But we don’t teach empty chairs. We teach kids who have needs, personalities and interests.”

Tyrone Johnson, who teaches third grade at Ashley, grew up without his dad in the picture, so he can empathize with many of his students. And while he loves the way kids react to him, presenting himself as a role model wasn’t an easy transition.

“When I first started, kids had issues with me being a strong figure, an authoritarian,” he says. “They’re used to hearing it from their moms or aunts. I had a learning curve.”

According to Colorado Department of Education statistics for 2009-10, male teachers made up barely 3 percent of kindergarten instructors, with that number gradually rising with each grade level to a peak of 30.4 percent in sixth grade.

Among the 10 largest districts, Douglas County had the lowest percentage of men teaching elementary school, at 11.2 percent, while Colorado Springs District 11 had the highest, at nearly 21 percent.

Denver Public Schools, at 17.7 percent, ranked second-highest among the large districts.

“Now, more than before, we are looking specifically on how better to recruit men,” says Jeannine Carter, director of diversity initiatives for DPS. When the district looks at out-of-state colleges to recruit, she adds, the male-female breakdown figures into any decision to invest in a campus visit.

“We don’t spend dollars where they don’t have larger mixed-gender populations,” Carter adds.

Recent University of Colorado Denver graduate Christian Eaves finds himself looking for a job in the primary grades while most of his male classmates head straight to high school or middle school, often lured by the added attraction — and income — of coaching sports.

He figures that even when he finds an elementary gig, he’ll seek a second job to bolster his bottom line. But the financial aspect hasn’t changed his commitment to teaching younger kids.

“I get a lot of ‘Why would you want to do that? Kids are crazy, and there are too many behavior problems,’ ” Eaves says. “And a lot of people say it’s an easy job — it’s like you’re a cop-out, not taken seriously. I tell them they don’t understand. You’re making an impact on somebody’s life.”

Men were fixtures at the lower grades until about the mid-19th century, after which their numbers plummeted just before World War I as job options for men expanded and women could be paid less, says Bryan G. Nelson, executive director of Men Teach, an organization that aims to increase men in the field.

Numbers rose slightly during the Depression, and then again after World War II, when the G.I. Bill sent a surge of soldiers into America’s classrooms.

Nelson thinks the country might be experiencing a slight uptick thanks to similar circumstances — a poor economy and military personnel returning from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Still, he adds, a recent survey by his organization showed that low pay and status, along with concerns about stereotypes and allegations of inappropriate behavior, continue to deter some men from elementary education.

“I don’t think there’s active opposition,” Nelson says, “though I do think you could find people who’d say, especially with the younger ages, that no, (men) don’t belong there. But I know it’s changing. There’s a shift going on in society.”

Margarita Bianco has seen such a shift, however subtle, in the pre collegiate class she teaches at Montbello High School.

Bianco, an assistant professor of education at UCD, offers the program — called Pathways2Teaching — primarily as a means to encourage students of color to consider careers in education. But she was pleasantly surprised to find 10 males among the 33 enrollees.

One of the program’s early projects involved pairing the high school students with fourth-graders at nearby Greenwood ECE-8 to help them learn vocabulary.

“Some of the (high school) students, especially the boys, said things like this was the first time in their life that they felt needed and special — they loved the idea of being role models for young kids,” Bianco says.

Interest isn’t so robust at the University of Northern Colorado, where professor Gary Fertig teaches two undergraduate classes on teaching elementary school social studies. This semester, for the first time in his 17 years at the Greeley school, no men are enrolled.

“I think the public considers (middle school or high school) to be more academically rigorous,” Fertig says. “In elementary school, you’ve got to be attentive to all (kids’) needs and emotional quandaries, because it all affects how they respond to your instruction in the classroom.”

Perceptions “hard to change”

His colleague Michael Opitz has one male undergraduate in a class of 30.

“Perceptions,” he says, “are hard to change.”

Opitz, who has authored textbooks on teaching, has found himself deliberately inserting men into his books’ hypothetical scenarios — just to counter the stereotype.

Fertig and Opitz note that UNC’s post-baccalaureate program, which allows students who already have a bachelor’s degree to fast-track toward a teaching license, has attracted more men than the undergraduate program. They see a combination of life experience and parenting experience dissolving some of the old stereotypes and producing a new pipeline of men for the elementary school classroom.

Metro State has noticed a similar trend, as post-baccalaureate male students seeking an elementary teaching license doubled the percentage for male undergraduates — 20.3 to 10.4.

Paul Frazier, 28, enrolled at Metro State after using his degree in criminal justice to work as a counselor in the juvenile system.

Disheartened by his experience with adolescents, and mindful that he saw no male teachers as he grew up, Frazier resolved to try to reach young kids before they took a wrong turn.

He’s currently student-teaching fourth grade in Aurora.

“The younger kids — now, they need us more,” he says. “Me being an African-American male, my parents always instilled that education is important. It’s hard working with other black youth and seeing that they don’t have the same reinforcement. That’s why I’m there, being a role model for them.”