Male teachers are rare in U.S. elementary schools

Most children go through elementary school under the charge of few if any male teachers, and local educators don’t like it.

Historically, the number of female schoolteachers has overshadowed the number of male schoolteachers. In fact, the numbers aren’t even close.

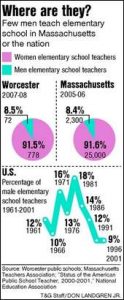

The National Education Association says the population of male teachers nationwide has been shrinking for decades. Roughly 21 percent of the country’s 3 million teachers are male, according to a 2004 NEA report.

The difference in elementary schools is even more striking: Only 9 percent of elementary school teachers are male.

Those figures are in line with what Mark T. Brophy, staffing mentor coordinator for Worcester public schools, has seen.

In Worcester, 778 women and 72 men, or about 8.5 percent, work at the elementary level, Mr. Brophy said.

In the Wachusett Regional School District, 177 women work in elementary schools, compared with 18 men, or about 9.2 percent, according to Susan H. Sullivan, director of human resources for the district.

The state Department of Education, which previously didn’t keep track of teachers by gender, began collecting those numbers this year and will report them in January, said DOE spokesman J.C. Considine.

In Worcester, Mr. Brophy has spent 22 years in public education, beginning as a kindergarten and second-grade teacher and later moving to the school system’s human relations department. Achieving gender balance in teaching staff is important, he said, because children don’t go to school just for academics — it’s where they develop social skills, too.

“Being able to see not just one gender in the classroom … I think it contributes to the healthfulness of a classroom,” he said. “It shows that communication works in various ways, and that the world is full of males and females, and we interact with each other.”

Kevin J. Brennan of Brookfield, a former chef who became a schoolteacher in Worcester last year, said many of his male students are excited to finally have a male teacher.

“A lot of these kids have never had a male teacher all the way through school,” said Mr. Brennan, who teaches sixth grade at Union Hill School. “It’s wonderful to finally have a male teacher and talk about football and other male things.

“A lot of the boys need a positive role model in their lives. I see that more in some of the economically challenged areas,” he said.

Anne T. Wass, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, said it’s important for young children to have positive role models, both male and female.

“I think it’s really important for boys to have positive male role models, as well as for the girls to see positive male role models,” she said.

Educators can’t pinpoint why so few men become teachers, but they agree that stereotypes are a big part of it.

“Historically, we don’t have any models of men as teachers,” said Patrick J O’Connor, associate professor of secondary education at Worcester State College. “It’s looked at as a feminized profession. And the students have grown up in a culture where they haven’t seen many teachers that are men.”

Bryan G. Nelson of Minneapolis, a former teacher turned male-teacher activist, puts it simply: “Young men think they don’t belong there.”

Mr. Nelson is the founder of menteach.org. He has conducted research in the hopes of deciphering the male teacher shortage, and has come up with three reasons.

They are, in no particular order:

– Stereotypes;

– Fear of accusation of abuse;

– Low status and low pay.

“People assume that teaching is for women, not for men, that men are not nurturing,” he said.

Some people assume male teachers are gay, just because they chose to become teachers, he added.

Sometimes misconceptions are serious. Mr. Nelson said many men are wary of becoming teachers because their interactions with children are easily misinterpreted or misconstrued.

“They have to think twice whether they hug a child or not. People hold you under suspicion,” he said. “Women teachers don’t hesitate to show warmth to a child.”

Mr. Nelson doesn’t like the argument that men don’t go into teaching because they need higher salaries to support their families. He contends that single mothers become teachers, even though they have to raise children on their own. Plus, plenty of men choose to pursue other professions — jobs such as police officers or the military, for example — that don’t pay much more than a teacher’s salary.

Mr. O’Connor said salary is an issue, but it’s not just an issue for men. Many talented young men and women who could be teachers instead are choosing jobs that pay more. The number of undergraduate students enrolling in the secondary education program at Worcester State College has dropped at least 40 percent in the last four or five years, he said.

The starting salary for public school teachers in Worcester is $38,838, according to Mr. Brophy.

Mr. Brophy said he loved the years he spent working as a teacher, but he was not free from “false perceptions.”

“Yeah, there were misconceptions of me,” he said. “Like, ‘Why do you want to go work in a preschool?’… We’re perceived as, if we’re giving a kid a hug, there is something wrong with us.

“That’s sad that people have those misconceptions. That’s sad and untrue,” he said. “Men can be just as caring as women.”

There are efforts nationwide to recruit schoolteachers, but few programs specifically target men.

The Cambridge-based Schott Foundation for Public Education recently announced that it will use a $1 million grant from the Deutsche Bank Americas Foundation to fund an initiative to recruit and retain African-American male teachers. Clemson University already has in place a program known as Call Me MISTER, which aims to recruit black male teachers.

There’s no reason men can’t make good teachers, said Mr. O’Connor, the Worcester State professor.

“There are men poets,” he said. “If men can feel free enough to identify with poetry and art, it’s funny that they don’t feel free to go into elementary school teaching.”