Tynita Johnson had attended predominantly black schools in Prince George’s County for 10 years when she walked into Will Thomas’s AP government class last August and found something she had never seen.

“I was kind of shocked,” said Tynita, 15, of Upper Marlboro. “I have never had a black male teacher before, except for P.E.”

Tynita’s experience is remarkably common. Only 2 percent of the nation’s 4.8 million teachers are black men, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In fact, Thomas, a social studies teacher at Dr. Henry A. Wise Jr. High School, never had a black teacher himself.

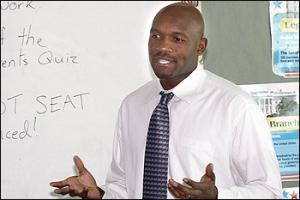

“I love teaching, and I feel like I am needed,” said Thomas, 33, of Bowie. “We need black male teachers in our classrooms because that is the closest connection we are able to make to children. It is critical for all students to see black men in the classrooms involved in trying to make sure they learn and enjoy being in school.”

The shortage of black male teachers compounds the difficulties that many African American boys face in school. About half of black male students do not complete high school in four years, statistics show. Black males also tend to score lower on standardized tests, take fewer Advanced Placement courses and are suspended and expelled at higher rates than other groups, officials said.

Educators said black male teachers expose students to black men as authority figures, help minority students feel that they belong, motivate black students to achieve, demonstrate positive male-female relationships to black girls and provide African American youths with role models and mentors.

“There are two axes in most American classrooms: a female axis and an Anglo cultural axis,” said Janice Hale, director of the Institute for the Study of the African American Child at Detroit’s Wayne State University. White girls fare best because they belong to both groups. White boys and black girls fit into one. “But black boys can’t get under the female or the cultural banner,” she said.

Howard University Provost Alvin Thornton, a former Prince George’s school board member who conceived a black male achievement program for students 15 years ago, said students who don’t see teachers who resemble themselves “grow up to think they don’t contribute to knowledge.”

“I think it is necessary that students be exposed to a knowledge transfer system that is diverse in terms of those who are transferring the knowledge,” he said. “And that diversity should look much like the community.”

Black males also leave teaching at a higher rate than their colleagues, according to a 2003 study by the National Education Association, a national teacher’s union. Half of black males leave the profession before retirement, compared with 30 percent of all teachers.

“There was a time when teaching was almost the only profession that African Americans could get into that would give them recognition, respect and a little salary,” said Reginald Weaver, a former NEA president. “As other areas of employment have opened up, many minorities entered into those.”

Thomas is bucking the trend. He was hired to teach middle school social studies in Prince George’s 10 years ago and moved to high school two years ago. He was chosen Prince George’s Teacher of the Year and Maryland’s 2009 Teacher of the Year, and he has no intention of taking more lucrative job offers that have come his way since.

“I remember when he taught at Kettering Middle School, where I was principal, that he was committed to staying in the classroom,” said Marian White-Hood. “He’d get mad if you kept bringing up moving into administration. He would say, ‘Doc, these kids need black male teachers in the classroom, and that’s where I want to be.’ ”

Several of Thomas’s students cited race as a factor in his students’ success.

“He doesn’t focus on being a black male teacher, he doesn’t talk about it, but it helps me,” said Claudius Solomon, 15, of Upper Marlboro, a student in Thomas’s government class. “Mr. Thomas is my favorite teacher because he makes learning about politics and all fun, but he’s also a role model for us.”

Tynita said she notices a difference in the way boys act in Thomas’s class. “The black boys talk a lot more. They participate a lot more,” she said. “They really interact with him a lot more than they do with the female teachers. You can tell that they relate to him.”

Local school districts compete to recruit the limited supply of black male teachers, and programs across the country encourage them as early as middle school to consider majoring in education.

Several colleges offer financial incentives for black male students who major in education. One such program, Call Me Mister, started a decade ago as a collaboration between Clemson University and three private historically black schools in South Carolina: Benedict University, Claflin College and Morris College. At the time, there were only 200 black male teachers out of 20,000 educators in the state, said program executive director Roy Jones.

“There were 600 elementary schools, and so even if you take one teacher per elementary school, it would mean that 400 schools didn’t have a black male,” he said. “We also found that many of the teachers were concentrated in a few school districts.”

Fifty black men have completed the program, and 150 more are enrolled. The effort is in 15 colleges, including similar programs at Bowie State, the University of Maryland Eastern Shore and Norfolk State. Longwood University in Farmville, Va., where 50 years ago segregationists closed schools rather than integrate them, is the only local college to offer Call Me Mister, Jones said.

The Maryland Board of Education has declared shortages of African American and male teachers for several years. In 2008, 4.3 percent of the state’s 59,789 teachers were black men, and 17 percent were white men. In majority-black Prince George’s, where African Americans were 53 percent of the teachers, 12 percent were black men.

In the District, which is also majority black, 18 percent of the 3,800 teachers are men, and 9.7 percent are white men. In Virginia, 2.6 percent of the 100,908 teachers are black males, and 16.4 percent are white men.

“We have very limited numbers of males,” said Maryland State Public Schools Superintendent Nancy S. Grasmick. “If you break it down more and talk about African American males, they are even more scarce.”

Prince George’s has received a grant to recruit blacks into teaching math and science. The county also has programs to attract professionals into the classroom and to develop black male teachers.

“In general, many of our young men have gone away from teaching as a breadwinning career for their families,” said William Hite, the Prince George’s superintendent. “We have to work to make it a more worthy option.”