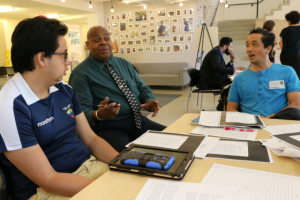

“Start sharing. Don’t be shy,” the facilitator said at the start a training last week for Asian, black, and Hispanic men hoping to teach in the New York City school system. He’d asked them to name a movie or song that spoke to them.

“Rocky,” one man said. “The Star-Spangled Banner,” said another. “Remember the Titans,” Kwang Lee said, citing the movie about the black coach of a racially mixed high-school football team.

“In our classrooms, we have a lot of diverse students,” explained Lee, 47, who worked in advertising for two decades before deciding recently to become a teacher. “We have to find ways to work together.”

In a city where Asian, black, and Hispanic boys make up 43 percent of the over one million public-school students, just over 8 percent of the city’s 76,000 teachers are nonwhite men. That leaves thousands of students of color without role models who resemble them, and without teachers who research shows tend to have higher expectations of nonwhite students.

The shortage is a national problem with many causes. Men of color who never saw themselves reflected at the front of the classroom may not consider teaching a career option, while others may balk at the pay or perception of teaching as “women’s work.” Others may enter the profession but face unwelcoming administrators or assignments and end up leaving.

Mayor Bill de Blasio wants to change this. Last year, he announced a $16 million program to add 1,000 new teachers of color by 2018. Called NYC Men Teach, the recruitment and training program kicked off this spring and includes a series of workshops such as the one that drew the prospective teachers to a Lower Manhattan office building last week.

One of the participants, Byron Fedele, had just earned his teaching degree from Brooklyn College when he saw a subway ad for the program and decided to join. Fedele, who is Guatemalan-American, said he was inspired by the opportunity to offer students something he never had growing up in the city: A man of color in the classroom he could look to as a role model.

“There were definitely lots of examples in textbooks, like Martin Luther King,” said Fedele, 24. “But there was no one living, breathing in the classroom. That’s different.”

Finding a few good men of color

Program staffers are searching near and far for teacher candidates.

Recruiters have traveled to Atlanta, Chicago, and Philadelphia, and spoken to students at historically black colleges. In New York City, outreach workers who helped parents sign up for pre-kindergarten are now pitching the teaching program to community groups.

Meanwhile, the city has called on Teach For America and its own Teaching Fellows program to help men of color without education degrees obtain alternative teaching certificates. And it has partnered with the City University of New York, the school system’s largest teacher pipeline.

Counselors there are encouraging male students in various departments to consider teaching, while also trying to help current education students cross the finish line and begin their teaching careers. That involves providing workshops on New York’s teacher-certification exams and free vouchers for the practice test. (In 2014, only 48 percent of aspiring black teachers and 56 percent of Hispanics passed the literacy portion of the exam, compared to 75 of white test-takers.) To inspire would-be teachers, one CUNY college held seminars on the history of men of color in education.

“Whatever we can do to support them and get them into the classroom,” said Jonathan Gaines, academic student support program manager at CUNY’s Hunter College School of Education.

“Whatever we can do to support them and get them into the classroom,” said Jonathan Gaines, academic student support program manager at CUNY’s Hunter College School of Education.

New York is not alone in trying to diversify its teaching ranks: about two-thirds of states have minority recruitment programs. They have a gaping hole to fill. Nationwide, over three-fourths of all 3.4 million public-school teachers in 2012 were women, while 82 percent were white.

In fact, those recruitment efforts have been highly successful, according to Richard Ingersoll, a University of Pennsylvania education professor. From 1988 to 2008, the growth in nonwhite teachers nationwide outpaced the growth of nonwhite students and white teachers, according to a report he wrote with researcher Henry May.

The more intractable problem is retention, Ingersoll said. Teachers of color are more likely than white teachers to switch schools or leave the profession, according to the report.

“If you don’t have some retention,” Ingersoll said, “we’re not really going to gain much ground.”

Searching for the right school

David Taylor, 46, has bounced around from one New York City school to the next over the past five years as a substitute teacher. He said he’s interviewed for many permanent positions, but rarely is called back.

He did once work as a full-time teacher in Las Vegas, but felt uncomfortable as one of only two black teachers at his school. During a staff meeting, his principal said some misbehaving students had been displaying “typical African-American behavior,” according to Taylor.

“It just didn’t feel like I was welcome there,” he said.

The object of Taylor’s search is similar to that of many male teachers of color: a school that will hire them for a classroom position and is also a place where they want to work.

That can be elusive, as nonwhite teachers are more likely to land in schools with many low-income students of color. Teachers at those schools often work with students who are struggling in class and facing hardships at home, even as the schools tend to have fewer resources than ones in more affluent districts.

In addition, administrators frequently pull nonwhite male teachers out of the classroom and assign them roles as disciplinarians or coaches, experts say. Even when they remain teachers, they often are enlisted as cultural translators for white colleagues, or informal counselors for students of color.

“We always have to be the conduits, the explainers,” said José Luis Vilson, an eighth-grade teacher at I.S. 52 in Upper Manhattan. Nonwhite students, he added, often “don’t feel like they have anyone else to turn to who gets it.”

Getting them into school — and keeping them there

As the program rounds up aspiring teachers, it’s working to help them land and keep good classroom jobs.

Staffers have taken men on school visits, and are hosting a job fair this month where they hope to introduce up to 400 would-be teachers with representatives from 100 schools. They will also match the men with current and retired educators who will help them polish their resumés and prepare sample lessons.

This summer, the education department is hosting a series of workshops like the one the men attended last week, on topics ranging from “culturally relevant” curriculum to personal wellness. It is also organizing panels where current and retired administrators can give the men advice.

Once the men find positions, the program will assign them mentors to help them navigate their first year in the classroom — a notoriously grueling period when teachers of all backgrounds are most prone to quit. And it will host gatherings of principals where they will discuss ways to hire more nonwhite teachers and help them flourish.

“When male teachers of color find schools where they have representation,” said Malik Lewis, an assistant principal at West Brooklyn Community High School, “they feel more secure, they feel more supported, and they stay longer.”

If the city is successful, students will soon be looking up to more teachers like Jian Xiao, 29, who recently signed up for the training program.

If the city is successful, students will soon be looking up to more teachers like Jian Xiao, 29, who recently signed up for the training program.

As a substitute teacher, he has been struck by how excited many of his students are to have a nonwhite teacher: Asian students eagerly speak with him in Chinese, while black and Hispanic students pepper him with questions about Chinese culture, he said. When he was a student in the city schools, he never questioned why none of his teachers looked like him.

“But as I got older,” he said, “I realized — why aren’t there men of color in the school system teaching?”