In his 14 years as a New Haven public-school student, Harold Cooper has never had a black male teacher. He’s not alone.

Harold, a 17-year-old Hillhouse High School senior, said he feels black male teachers can “relate more to the students.” He doesn’t know for sure, because in all of his schooling since pre-K, he has never had one.

His story is emblematic of a persistent national trend: The gap between the number of minority kids and the number of minority teachers is getting wider. And black male teachers are especially hard to find.

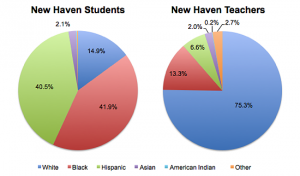

New Haven, like many cities, has a jarring mismatch between the student population and the teaching workforce: 85 percent of students are racial minorities, and 85 percent of teachers are white.

The shortage of minority teachers is even more severe for men. Out of 1,883 active teachers on file in the district, only 56 are black men, according to the school district’s latest figures. Black males make up 3 percent of the teaching workforce, but 22 percent of the 20,938 students in New Haven public schools. Hispanic men are also scarce: In New Haven, only 23 teachers are Hispanic men.

Those facts put New Haven roughly on par with the rest of the country: Less than 2 percent of U.S. teachers are black males, according to the U.S. Department of Education. The same goes for Hispanic males. Male teachers are hard to come by: three-quarters of teachers in New Haven, and nationally, are women.

Former Superintendent of Schools Reggie Mayo said the number of minority teachers in New Haven has dramatically dropped—from 33 percent to 15 percent—since he took office 21 years ago. Mayo, an African-American who rose up the ranks from substitute-teacher and janitor to superintendent, said he’s “very concerned” about that trend, because kids need role models who look like them.

Former Superintendent of Schools Reggie Mayo said the number of minority teachers in New Haven has dramatically dropped—from 33 percent to 15 percent—since he took office 21 years ago. Mayo, an African-American who rose up the ranks from substitute-teacher and janitor to superintendent, said he’s “very concerned” about that trend, because kids need role models who look like them.

“This is an issue that I am really conscious of,” said schools Superintendent Garth Harries, a white man who took over from Mayo in July. He vowed to address the problem in part by making New Haven stand out as a place where teachers can take on leadership roles that don’t exist in other towns.

The issue gained public attention last week, when the school district chose a black male teacher, Garfield Pilliner, as its teacher of the year.

Some said the shortage of men like Pilliner in the teaching force is a grave concern for black boys, who are more likely to drop out of school, face unemployment, and—in Connecticut—12 times more likely to end up in prison than their white peers.

Pilliner worked at Bridgeport’s Harding High before joining New Haven public schools in 2009.

Pilliner worked at Bridgeport’s Harding High before joining New Haven public schools in 2009.

“The sad part about this article is the students who need him most like the young man at Harding High will more likely never have another black male teacher in his educational experience in Connecticut,” a reader named “keep it real” in the Independent comments section to a story about Pilliner’s honor. “You can’t be what you don’t see. Until we start demanding Connecticut find ways to put ‘qualified’ men of color in the classroom, the school to prison pipeline will continue.”

Educators interviewed for this article offered varying opinions—but no easy answers—on how to recruit and retain more black men, as well as men and minorities in general, to the teaching force.

The Shortage

The scarcity of black male teachers—56 across 47 schools—is felt across the district, and more acutely in elementary schools. Hill Central School, where a quarter of kids are black, has only one black male teacher, according to Principal Glen Worthy (pictured).

Worthy said that’s not for lack of trying.

In June of 2010, Worthy got a rare chance to replace half of his staff as part of a quiet “turnaround” effort financed by a federal School Improvement Grant. He replaced all of the teachers except one in grades 3 to 8. He had 21 openings. He kept an eye out for black male teachers.

“I was looking hard,” said Worthy. “I couldn’t find any.”

Another school, High School in the Community, pushed out its only black male teacher through the same “turnaround” process and did not bring any more in.

Another school, High School in the Community, pushed out its only black male teacher through the same “turnaround” process and did not bring any more in.

Hillhouse High, where 75 percent of students are black, has only four black male teachers out of 87, according to Principal Kermit Carolina.

Worse than the scarcity of black male teachers, Mayo said, is the shortage of bilingual teachers. At one point, he said, the school district had 17 vacancies for bilingual teachers.

Mayo said the lack of interest in the job among minorities is apparent at an early age. He recalled going to classrooms of young city kids and asking, “Does anyone want to be a teacher?”

Mayo said the lack of interest in the job among minorities is apparent at an early age. He recalled going to classrooms of young city kids and asking, “Does anyone want to be a teacher?”

He would see maybe one hand rise. “I don’t know what the problem is,” he said.

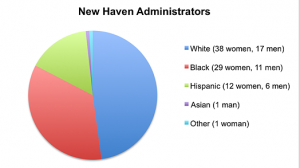

The district has done much better at fielding minority administrators, Mayo noted: “We can pluck them out of the teaching force.”

Blacks comprise 35 percent of school administrators; Hispanics comprise 16 percent. Lately, finding more minorities to promote to administrative jobs has been difficult, he said.

Contrary to widely held opinion, recruitment of minority teachers has been “very successful,” according to a 2011 analysis by Richard M. Ingersoll and Henry May of the University of Pennsylvania. The number of minority teachers has almost doubled in the past two decades, they found. But minority teachers tend to work in high-poverty schools, and thus have higher turnover rates than their white counterparts, they concluded.

The number of minority teachers has failed to keep up with the increasing number of minorities in U.S. schools, Ingersoll and May determined. The gap has been growing in the past three decades. Now minorities comprise 40.6 percent of public school students, but only 16.5 percent of teachers, they found.

Does Race Matter?

Harries said New Haven “absolutely” needs more minority teachers, and male teachers, too.

Harries said New Haven “absolutely” needs more minority teachers, and male teachers, too.

“All teachers need to be able to build relationships with students of different backgrounds,” he said. “There are certainly white teachers, and female teachers,” who succeed in doing that. The district needs to help all teachers do the same, he said.

But it’s also important that the teaching force “reflect the students it serves,” Harries argued.

African-American educators interviewed for this story cited two main reasons race matters in the classroom: Black teachers are better able to relate to black kids; and black kids need black role models to illustrate what’s possible for their own lives.

Teacher of the Year Pilliner, who’s 36, said said he has seen—and shown—how a black male teacher can be a powerful mentor in a black boy’s life. From 1992 to 1996, when he was a student at West Haven High, he said, there was one black male teacher in the building. That man was a familiar face, someone to talk to about life beyond school. He said beside that man, “I felt I had no one to talk to.”

At Engineering & Science University Magnet School, Pilliner has adopted a crew of black boys who come to him for advice. In a short hour last week, a half-dozen stopped by to see him.

“Yo, Pilliner!” they sometimes call to him from the hall. He said he doesn’t take it as a sign of a disrespect. “It’s just how we demonstrate a level of relationship.”

He said he seeks to send a message to black boys looking to launch careers: “If Pilliner can do it, I can do it.”

Fred Redeaux, an African-American math teacher at Hillhouse High, said he feels he can relate to his students because of a shared background, of which race is one part.

“I grew up in Chicago. I was in a gang,” Redeaux said. That helps him relate to the tough circumstances kids are facing at home—and help them see a way out.

David Johnson, a junior at Hillhouse, agreed. He said he has had one black male teacher in his New Haven public school experience, which began in pre-K.

“The one I had,” a history teacher who has since retired, “taught us a lot—even beyond the subject he was teaching,” David said. They talked about college and heading out into the world as a black man: “You need to qualify just as well as anyone else does,” the teacher told him. David said he felt that sharing a race, gender and common experience helped them build a stronger relationship.

Harold, the senior at Hillhouse, said he thought having more black male teachers might stop black boys from dropping out of high school.

Others downplayed the importance of race in the classroom.

“Having a black male teacher in front of a black student may be inspiring or symbolic,” said Hillhouse Principal Carolina. But it “does not automatically translate into success for that student. … It has been my experience that the color of your skin does not matter to a kid who is looking for a positive adult mentor in their life” who supports the student and raises expectations.

Alex Sinclair (pictured), 43, an African-American history teacher at Hillhouse, said he initially thought a teacher’s race was an important factor in the classroom. Then he started teaching at a technical high school in Torrington. He said he was apprehensive about it at first, but found he could connect easily with the predominantly white students.

At Hillhouse, where most of his students are black, his race does not make him more effective, Sinclair said: “I don’t think my blackness commands respect” among kids, nor furthers “any sort of policy in the classroom.”

Sinclair, of Bristol, said he grew up attending Catholic schools that had “not one black teacher,” yet he still became an educator. “I’m not sure it matters” to have role models that look like you.

“It doesn’t really matter if there’s an African or Caucasian” in the classroom, said Tyrell, who has never had a black male teacher. The important thing, he said, is to “keep it going,” to keep education passing through generations.

Why So Few?

Why aren’t there more teachers like Mr. Sinclair?

Sinclair offered two reasons more black men don’t enter the profession: status and pay.

“My father even looks at me with a degree of disdain,” Sinclair said. “He doesn’t look at me as a success,” but as a “glorified babysitter.”

Sinclair, a UConn grad who once aspired to be a theologian, could have earned more prestige and money in the corporate world—especially as corporations actively seek minorities. Many of his friends have gone that route. He said teaching isn’t equipped with the same kind of compensation systems that reward hard work.

Superintendent Harries said one reason more minorities don’t go into teaching is that other careers have opened up to them. “Teaching was one of the first professional career opportunities” that opened up to minorities, he said. As other industries accepted and recruited minority candidates, they drew those candidates away from teaching, he said.

Harries said the district’s teaching workforce “reflects the applicant pool.” Over time, the district has been getting fewer and fewer black or Latino applicants, he said.

Redeaux, who teaches math at Gateway Community College in addition to Hillhouse, said black males don’t tend to major in education in college.

At Southern Connecticut State University, which provides many teachers to New Haven schools, 80 percent of students in the teacher prep program are white, and 75 percent are female, according to university spokesman Joe Musante.

Researchers Ingersoll and May, however, argue that the main problem isn’t recruitment, but retention.

A survey of over 50,000 teachers found that the biggest reason minority teachers choose to leave the profession is “organizational conditions,” such as whether they had autonomy in the classroom and input in how the school was run, the researchers found. Other top reasons are pay, professional development and classroom resources.

What To Do?

Former Superintendent Mayo said he has tried several experiments to get more minority teachers into city schools. One involved two groups of paraprofessionals who were already working in New Haven schools. The first group comprised 18 teachers aides. The school district sent them to Gateway. They graduated from Gateway and got certified to teach, but most of them had to find part-time work instead of full-time teaching gigs once they graduated, he said.

Mayo also pointed to Hillhouse High’s teacher prep program, through which kids get practice teaching at Wexler/Grant School.

The program currently includes kids like Jarrad McCown. (Jarrad, pictured, is also the lieutenant colonel battalion commander of Hillhouse High’s Junior ROTC.) Jarrad, who’s 18, said he got interested in teaching through his grandmother, who works at King/Robinson. He said he plans to teach high school history, then get a doctorate in education and become an administrator.

The program currently includes kids like Jarrad McCown. (Jarrad, pictured, is also the lieutenant colonel battalion commander of Hillhouse High’s Junior ROTC.) Jarrad, who’s 18, said he got interested in teaching through his grandmother, who works at King/Robinson. He said he plans to teach high school history, then get a doctorate in education and become an administrator.

One challenge, Mayo said, is helping kids like Jarrad make it through college. New Haven public schools launched a partnership with SCSU to try to encourage more city kids to go into the profession. SCSU offered five scholarships to kids in the teacher prep program. The problem was that once the kids got to college, most of them ended up switching majors, Mayo said.

Mayo suggested revisiting those two programs—the paraprofessional pipeline and the scholarships at SCSU—to make them more successful.

Mayo said he thought the election of the nation’s first black president would help spur young black men to aim high with their lives. But kids need more black male role models, including teachers, he said.

“President Obama can’t do it all,” he said. “He’s not there every day in the classroom.”

Hillhouse Principal Carolina called on “parents and the community at large” to “celebrate the academic achievement of black males with equal or more enthusiasm than they display when celebrating their athletic achievements.” That would “encourage more black males to value their intellect and not just their physical capabilities.” It would also encourage more black males to go into “intellectual careers like teaching.”

When qualified minority teaching candidates emerge, competition is fierce among school districts to hire them, Harries said.

Harries cited one area that may give New Haven a leg up in that competition: Creating leadership roles for teachers. The school district has created new “pipelines” for teachers to develop into principals, as well as new opportunities for teachers to become leaders without leaving the classroom.

A recent report by the Center for American Progress offered a few more ideas: Create statewide initiatives to attract low-income and minority teachers into teacher prep programs. Hold teacher prep programs more accountable for making sure low-income and minority students graduate. Give those students more federal financial aid in college. Reduce the cost of becoming a teacher. And strengthen alternative routes to certification.

A Second Career

Another place to look for minority teachers is in other industries, Mayo said. New Haven has succeeded in finding black men to join teaching as a second career.

Redeaux (pictured), now a popular and dedicated teacher at Hillhouse, started his professional career working a lab tech at Kodak. He said he has always been a teacher of some sort. When he was an undergraduate at Gateway, he started teaching calculus to middle-schoolers in the basement of St. Luke’s Church on Whalley Avenue. And in chemistry class at Gateway, he would “translate” the teachers’ instructions to other kids in his class.

He made a mid-career switch because of external forces: The product he had been working on at Kodak was being moved to St. Louis. He had two options: Move there, or change his job. He decided to go into teaching as a profession. He’s now in his 15th year teaching high school.

“Now, it’s not like going to work at all,” Redeaux said. “Even when I’m sick, this is where I prefer to be.”

Like Redeaux, Pilliner didn’t start as a teacher. He had been on the path to become an engineer, but he didn’t like it. He said he started teaching only because “I was invited.”

A friend who taught at Harding High in Bridgeport recruited him.

“Because you’re my best friend, and I trust you, I’m going to come,” Pilliner recalled telling his friend.

He suggested teachers use social networks to draw more minorities and men into the profession.

Sinclair, who’s been teaching for 17 years, also came to the profession from a roundabout route. A guitar-player and singer-songwriter, he toured with his indie rock band after attending UConn. He joined teaching because his dad gave him an ultimatum: “Move out” or get a real career. Sinclair said he was initially attracted to teaching because of the summers off.

“I’ll have time to work on my music,” he thought. He was wrong: Teaching became his life. And it became his passion.

Now, he said, he doesn’t see himself doing anything else.