At Martin Luther King Elementary School, female teachers outnumber males by almost three to one.

In that regard, teachers at the Clayton County school say, MLK is not that different from most schools across the country, where places of learning can seem like female-only clubs.

There are signs, however, that the long-standing trend may be changing. Principal Machelle Matthews has made a conscious effort to recruit and retain black male teachers.

Matthews, teachers say, has created “a climate and culture of success” not often seen in predominantly African-American schools.

Kerry Meadows — one of 14 males among 60 teachers — believes the effort is critical to the success of all of MLK’s students but boys in particular.

“We’re in a community where socially we have to recognize the absence of fathers in the home,” said Meadows, a 50-year-old former naval officer. “Having males in the classroom fills that void and exposes students to an authority figure they don’t often get to see.”

Having a male presence at the school also motivates students to excel, he said.

Nearly half of all black male students drop out of high school nationwide, statistics show. In addition, they tend to score lower on standardized tests and are suspended and expelled at higher rates than other racial groups.

Although the percentage of male teachers across the state is growing — from 17.9 percent in 2002 to 19.3 percent in 2008 — officials say there is no concerted effort to increase the number of men — black or white — in classrooms. They say it’s quality that matters, not gender.

In Georgia, 22,976 of 119,018 teachers are males, according to figures from the Georgia Professional Standards Commission.

In Gwinnett County, the state’s largest district, men account for 17 percent of teachers. The percentages are similar in Cobb and Fulton schools. Around the country, efforts to increase the presence of male teachers, and black men in particular, are growing. In addition to programs that encourage males to consider education as early as middle school, several colleges are offering scholarships to black men who major in education.

Two such programs are MenTeach and Clemson University’s Call Me MISTER, the latter created to address the shortage of black male elementary teachers in South Carolina.

Call Me MISTER has successfully graduated and placed more than 50 men in the classroom, said Roy Jones, the program’s executive director. About 150 are in the pipeline, he said, attending one of 15 colleges in South Carolina. Another 15 are enrolled in six other states, including Albany State University in Georgia.

Although men tend to shy away from teaching because of low pay, stereotypes and fear of abuse allegations, Bryan Nelson, the director of MenTeach — an advocacy group for male teachers — believes that will soon change.

As more women go into nontraditional professions, men are also shifting to nontraditional occupations such as nursing and education, he said.

“This is not about men versus women,” Nelson said. “Children respond to and want to be around men. They want to emulate men, to see how they behave.”

When Matthews opened Martin Luther King Elementary six years ago, she knew immediately she had to deal with the absence of men at school. Nearly 90 percent of its students were African Americans from single-parent households, she said.

She wanted to create an environment where students could see male teachers and where dads, granddads and uncles could feel welcome.

Matthews wanted male teachers who could move student achievement beyond the standards, who were willing to show up in a shirt and tie and who would agree to mentor one or two kids.

At one point, there were 26 new teachers who’d just graduated from college.

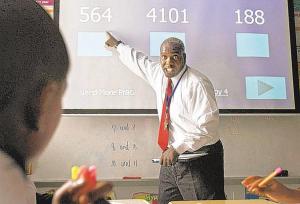

Xavier Woods, a 29-year-old graduate of Valdosta State, was one of them.

The baby-faced teacher was happy to sign on with Matthews.

“I really feel like I’m changing the world in Room 216,” he said.

Indeed, Woods’ influence and that of his 13 co-horts stretch beyond MLK’s walls.

Each year, the men host a father-daughter dance and run programs like the school’s mentoring organizations.

The results speak for themselves. The College Park school has earned a spot on the state’s Annual Yearly Progress list as a top-performing school every year since it opened. Disciplinary problems are almost nonexistent.

While no one discounts the female influence at the school, they say the impact of more male teachers is undeniable.

When one of Michael Coats’ fifth-grade social studies pupils asked him why he had on “church clothes,” he knew he was in the right place.

“This kid had never seen a man in a shirt and tie outside of church,” he said.

“They know they can talk to me and I think they appreciate that,” said Coats, 40.

Shawnya Wymbs, a single mother of three, requested a male teacher for her son as his third grade year drew to a close.

Although Joshua has a good relationship with his father and grandfather, Wymbs swears by the male presence at Martin Luther King. “He’s always had female teachers, excellent teachers,” she said, “but when boys get to be a certain age, they need a male influence.”