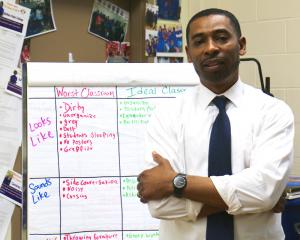

Christopher Fields is rare in the teaching profession. He’s an African-American man, and he teaches sixth-grade English at East Lower School. According to the U.S. Department of Education, you’d have to stop by more than 50 classrooms in this country before you found one black male teacher.

“We have a lot of African-American male students who – they need that interaction with a male,” Fields said. “Because they may not live in a two-parent home. So sometimes they just need that interaction. You know, they live at home with Mom, most of their teachers are female, and it’s just a refresher for them to see an African-American male.”

The Albert Shanker Institute recently issued a report on the gap between teaching and student diversity in nine large American cities. The city with the largest gap was Philadelphia, with 86 percent students of color, and 31 percent teachers of color. That’s a gap of 55 percentage points. Had Rochester been included in the study, it would have ranked first, with a gap of 65 percentage points. Rochester students of color make up 90 percent of the school population, but teachers of color comprise just 25 percent.

American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten responded to the Shanker study by calling for a national summit to address teacher diversity in urban districts. “When there’s a diverse teaching workforce, all kids thrive,” Weingarten said in a statement. “That’s why we note with alarm the sharp decline in the population of black teachers in our cities.”

Fifty-nine percent of Rochester city students are black, but that’s true for only 16 percent of teachers. Fields says that gap has a serious impact on students.

“What I always tell my students is, ‘I’m teaching you skills that are beyond the academia. Just how to communicate, and how to live, and how to treat others’ – is an important piece that I think some teachers are not comfortable with because of the cultural divide,” he said.

There is a wide body of research that supports this idea. For example, researchers at Georgia State found in 2007 that when students of color had more teachers of color, they not only showed up for class, but they also followed through to graduation more often. Researchers in Tennessee found that in just one year, students who were assigned to teachers of the same race increased their math and reading scores by four percentage points.

India Quick, a junior at East Upper School, has always loved math – but she couldn’t quite excel in it. That is, until eighth grade.

“I had, like, C’s, and then they went up to A’s when she switched in to my class,” she said.

The “she” is Ms. Morales, a teacher of color who not only helped India raise her grades; she’s helped inspire India to see herself as a future teacher.

“We had a great connection with each other, ’cause she went through things I went through,” India said. “And I still talk to her to this day.”

India joined the Teaching and Learning Institute, or the TLI. The 20-year-old program is designed to groom students for careers in teaching. At East, two teachers and a counselor came through the TLI program. India already has had the chance to work in the classroom.

“We’re like student teachers,” she explained. “We help the teachers out. And I had kindergarten last year – I love that class. It’s like every student has a different personality, and it’s fun.”

Rochester Teachers Association president Adam Urbanski says the TLI is a small but vital effort.

“At the Teaching and Learning Institute, you’re now getting not only prospective teachers of color, but you’re now getting prospective teachers of color who know this community,” Urbanski said.

So-called “grow-your-own” programs like TLI represent the first step in Urbanski’s plan to reduce the district’s diversity gap, which Urbanski described as a “long-standing and long-neglected problem.” He offered two other ideas to change it.

Urbanski contends that the teaching profession has become unpopular, and he blames the recent battles with elected leaders like Gov. Andrew Cuomo. As an example, last year Cuomo said during a speech about education, “Right now it is virtually impossible to fire a teacher. The school districts will tell you they don’t even try anymore.”

Urbanski believes that kind of rhetoric is contributing to a decline in enrollment in teaching certification programs. And while supporters of reform say the governor is right, Urbanski says the profession won’t become more appealing until this kind of public battle subsides.

Finally, Urbanski advocates aggressive recruitment of minority teaching candidates in places like Puerto Rico and historically black colleges.

“Let me tell you that this isn’t going to be fixed real quickly,” he said. “So while we work on it, we have to do more with the staff that we currently have. It is reasonable to expect that white teachers who come from different socioeconomic status – that they must be willing to learn about their students. We can’t say that white teachers can’t teach students of color. Of course they can, but we have to emphasize training and support for them.”

Harry Kennedy leads the city school district’s human resources. He says the district is trying to recruit teachers of color through the Uncommon Schools program, which targets college juniors for summer teaching fellowships. Additionally, Kennedy touted a grow-your-own program of a different kind.

“Growing our own means looking at folks who are in the per diem substitute database,” he said. “You have a lot of minorities and diverse populations in that pool. What would it take to transition them from non-certification to certification, and bringing them full-speed into the teacher pool?”

Christopher Fields says that it’s important for all teachers to show empathy for students – without lowering standards.

“I know to keep the expectations higher for the students that I teach, or the students I interact with, because I know that sometimes people want to give them a break based on the inequities,” he said. “My kids know that, ‘Mr. Fields, he’s all right, but I have to stay sharp.’ It helps them to know that I care, and I expect the best from them.”

He knows it can work. This is a district with huge numbers of kids growing up in poverty, and he tries to keep them focused on their own success.

“I have had students who have said, ‘Mr. Fields, I’m gonna do it for you,’ ” he said. So how does Mr. Fields respond when he hears that?

“I’m like, No. I’m flattered, but do it for you.”

All data in this story is from the 2015-16 school year.