David Brown: From Black Male Teacher to Principal

When David Brown was in 6th grade at Mount Calvary Catholic School in Forestville, Maryland, he had his first male teacher. Brown — now principal at Hillcrest Heights Elementary in Temple Hills — grew up in a stable home with a father, but he says it was “foreign” to him to see a man in the role of an educator.

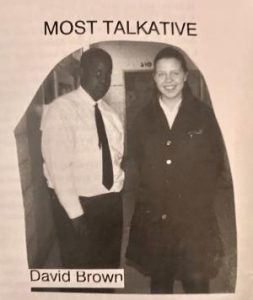

A basketball player who wanted to be a doctor or an NBA player, liked girls and disliked “dull people,” according to his 8th grade yearbook, Brown says having Stephen Newberg as a teacher “was impactful” and influenced him to pursue education as a career.

“I always wanted to help others,” he said. “Who better to help than a child?”

“I always wanted to help others,” he said. “Who better to help than a child?”

His parents pushed back, asking him how he would survive on a teacher’s salary. But he laughs now at those well-meaning words of advice. “We made it,” he says.

With only one male teacher and two male paraprofessionals at Hillcrest Heights, adding more men to the staff is one of Brown’s goals. He says boys “need models,” and interacting with male educators can help them learn to “regulate their emotions” and “deal with situations that are outside what they normally see at home.”

A year on ‘pause’

Brown was one of more than a dozen new principals in Prince George’s County Public Schools last fall and among hundreds who have been through the district’s leadership preparation programs. One of six large, urban districts to participate in the Wallace Foundation’s Principal Pipeline Initiative, the district developed a suite of administrator training programs as a way to be more selective in choosing school leaders and deliberate about how they are trained and supported.

But while Brown’s first year as principal may be over, it’s not complete. The pandemic “put a pause” on his full journey of welcoming students on the first day of school and closing “that chapter when you open that door one last time” for the summer, he said.

The crisis has Kristi Holden, the district’s director of professional learning, wondering how to adapt the leadership development programs for educators who may be stepping into their new role this fall from a home office.

“How do you build a culture through that? How do you build trust with a community virtually? It’s hard enough in-person,” she says. “Who knew when we walked out on March 12 that we wouldn’t be coming back?”

Some principals in the district also lead schools with staff members who have died from COVID-19 — or have had family members die — so being sensitive to teachers’ emotional well-being will get more attention. And even though the field in recent years has shifted toward an emphasis on principals’ responsibility for instruction, protocols such as fever checks, cleaning routines, mask requirements and whether students are violating social distancing rules will become a larger focus of their jobs this fall.

“Operations come to the forefront,” Holden says.

Rodney Henderson, who leads the district’s two-year principal induction program, said leaders are also discussing whether principals entering their second year this fall may need some additional support over what the program usually involves.

“We realize that the newness to the principalship in the midst of a worldwide pandemic called for new principals to acquire additional skills and operate in a manner that their predecessors were not required to do,” he says, adding that newer principals were challenged with learning how to “manage themselves more closely and truly value how they spent their time.”

For those school leaders who adhere to systems and structures — and Brown is one of those — the transition to distance learning “caused much less angst,” Henderson said, and the “areas needing improvement revealed themselves very quickly.”

Brown’s early attention to processes such as collaborative planning, professional development and data analysis paid off.

“He has always understood and been well prepared in the technical aspects of the principalship,” Henderson said. “These unusual times challenged him to apply technical knowledge to an adaptive school climate and community.”

A need for continuity

Recent survey data from the Learning Policy Institute and the National Association of Secondary School Principals shows a large segment of high school principals — 42% — are considering leaving their position, and some observers have suggested older educators might be inclined to retire rather than remain in the profession during what is expected to be a turbulent school year.

But Holden says she’s hearing the opposite sentiment from some PGCPS principals who could be eligible for retirement. One administrator expressed to her that it was important to provide students with continuity this fall in whatever way schools operate.

The RAND Corp.’s evaluation of the Wallace Foundation’s work on school leadership showed schools with principals who were placed as part of the Principal Pipeline Initiative had higher student achievement in both reading and math compared to a control group of similar schools. And retention rates among principals in the initiative were higher than those among other newly placed school leaders. Later this month, RAND will also release additional results from a survey of district leaders about their experiences with and interest in principal pipeline programs.

Additional, recent research on school turnaround efforts in Tennessee — comparing state-run Achievement School District schools with district-run Innovation Zone schools — also shows principal effectiveness is one factor contributing to higher student achievement in the iZone schools.

“This suggests that recruitment and retention of effective staff should be a main focus of plans to improve the lowest-performing schools,” the researchers wrote. They note even if the turnaround model calls for replacing staff members, such efforts “should attend to retaining effective teachers and principals after they are recruited to the turnaround school in the first year.”

Lifting spirits

Last fall, Brown arrived at Hillcrest Heights with the ambitious goal of seeing 7% to 8% growth in every grade level in both reading and math. While state tests were canceled this year, Alvita Jeffers, the school’s data coach, says the staff will look at county assessments and other feedback from teachers to determine the impact of the closures on students. Teachers, she said, focused lessons on a “mixture” of maintaining the students’ skills and introducing new material.

Brown’s message to the staff in the final weeks of school was to do as much as possible to “move kids as far as we can,” he says. “We can’t afford to take a dip.”

The school also distributed 260 devices to students — more than half of the school’s enrollment — and surveyed parents on internet access. The closure, Brown says, forced staff toward technology integration, a change he wanted but didn’t expect to happen so quickly.

The school also distributed 260 devices to students — more than half of the school’s enrollment — and surveyed parents on internet access. The closure, Brown says, forced staff toward technology integration, a change he wanted but didn’t expect to happen so quickly.

Brown — who usually tweets and signs his emails with #HawksFlyHigh, for the school’s mascot — has also worked to “lift the spirits” of his staff, sending them weekly “smile through it all” messages and cartoons. What he doesn’t mention, however, are the extensive steps he took to keep morale up during the three-month closure. And his “hands-on” approach to those technical aspects of school leadership also extended to his support of teachers, Jeffers says.

He organized virtual “Hillcrest Heights huddles” for staff members to share their experiences. And for Teacher Appreciation Week, he organized remote versions of a Jeopardy game, Name that Tune featuring teachers’ favorite songs, a scavenger hunt and a cookout.

“Mr. Brown tried his very best to be ‘virtually’ creative,” says Assistant Principal Sharon McNeil. “Teachers stated how appreciative they were of his efforts to recognize them during the week.”

He also sent everyone a card in the mail.

“Most people don’t understand what goes into teaching, and the work that’s happening in the building is now also happening out of the building,” Brown says. “While we weren’t prepared for this, we can stand on the platform that we are making a difference.”

June 16, 2020