From NFL to nanny

Politely but firmly, Mr. Clarke explains that he had spoken his piece in numerous telephone conversations starting in February. Now, six weeks later, there is nothing left to talk about.

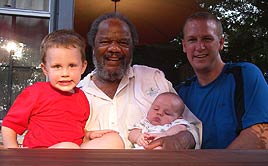

Besides, he has work to do inside. Behind the front bay window, a young mother cradles her infant son. Her older son is busy at the dinner table.

The children are Mr. Clarke’s work. Franklin, as he is known in this neighborhood, is the gray-bearded nanny to Quinn, 5, and MacAllan Clarke Tugwell, 1.

Once upon a time, the nanny was the most prolific receiver in Cowboys history. He was fast, smart and determined to prove wrong critics of his toughness. He joined a ragtag expansion team in 1960 and was the last original Cowboy to retire. The NFL Championship Game of 1967, the storied Ice Bowl, was his final game.

Mr. Clarke’s career had been largely archived until last fall, when Terrell Owens approached his team record for touchdown catches in a season, set in 1962. Mr. Owens’ record-breaking 15th scoring catch came down Interstate 85 in Charlotte. Mr. Clarke, invited by the Cowboys to make the 150-mile trip, chose to watch the game on television.

More Cowboys

Mr. Clarke did do perfunctory media interviews via telephone at the time. Mostly, he said he was happy for Mr. Owens. If he mentioned that he found his calling as a nanny after reinventing himself in the mid-1970s, it went unreported.

In the course of the reinvention, he divorced the mother of his three children, gravitated to the Living Love Center in counterculture Berkeley, Calif., and lived in a Kentucky commune blissfully named Cornucopia.

“I’m one of the luckiest people you ever imagined knowing, not having plans for any of this,” Mr. Clarke said in a general discussion of his life back in February.

In the series of phone interviews with The News, Franklin Delano Clarke, born during the inaugural term of the 32nd president, outlined a most unusual life. He preferred, however, to let specifics rest in peace.

Questions about Living Love, Cornucopia and his decades-long experiences as a nanny were dismissed. His stock reply: “I’ve already told you about that.”

For the record, Mr. Clarke has been a nanny for more than a quarter of a century – the last four years in the home of Jennifer Weaver, an attorney, and her husband, Todd Tugwell, an environmental consultant.

Previously, Mr. Clarke was the first black football player at the University of Colorado. He was the first black star on a Cowboys team playing in racially divided Dallas. He then became the first black sports TV anchor in Dallas and the first black NFL analyst at CBS.

At home, he was a doting father of two sons and a daughter whom he and his wife, Sandra, reared in the strict Catholic tradition of his childhood.

Even before Mr. Clarke retired from football, newspaper articles in 1966 speculated about a run at the Texas House to become the first black state representative since Reconstruction. But he decided politics were not for him.

Still, in the wake of the 1968 assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Dallas Mayor Erik Jonsson enticed Mr. Clarke to serve as coordinator of the city’s Council for Youth Opportunities.

“We all thought the sky was the limit for Frank Clarke,” said Pettis Norman, a former Cowboys teammate whose family once lived next door. “I know he is happy now doing what he is doing, but he is eminently qualified to do other things. It has been such a transformation.”

Life-changing moment

Mr. Clarke has shared few details about that transformation with former teammates, old friends or even his children. Most still have questions. Many have sparingly seen him. All are happy Mr. Clarke has found contentment.

“It has never been important for me to ask why he walked away from everything he knew,” said his youngest son, Jeffrey, 51, who lives near San Diego and has seen his father once since graduating from high school in 1976. Still, he calls his father “a remarkable man.”

Daughter Stephanie Pelton says her father’s Christian beliefs have led him to want to work with children.

“My dad is in love with the Lord,” she said. “He knows children will lead us.”

On the phone, Mr. Clarke talked sparingly about his own family and life after they left their east Oak Cliff home, where quarterback Don Meredith would often strum his guitar after games. Mr. Clarke headed to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1973 to work once more for Cowboys owner Clint Murchison, who once promised Mr. Clarke a post-football job for life, in corporate communications.

Mr. Clarke said he underwent the life-changing moment that allowed him to discard the shackles of his past a year later. On his 40th birthday, unfulfilled by his lot in life, he received the gift that became his road map to true happiness.

The Handbook to Higher Consciousness was a pop-culture best-seller written by paraplegic self-help guru Ken Keyes. In those 215 pages, Mr. Clarke discovered how to live with no facades or inhibitions.

The book eventually led Mr. Clarke, who divorced in 1976, to Mr. Keyes’ Living Love Center, a converted fraternity house on the fringe of the University of California at Berkeley. Living Love irritated its neighbors before it outgrew the frat house in 1977 and was moved to a former convent in rural Kentucky. Mr. Clarke, a regular visitor at Living Love, followed the next year.

On the 150-acre commune christened Cornucopia, the former Dallas youth counselor was eventually assigned to child care. When the commune fragmented, his connections led to life as a live-in nanny, mostly for the children and relatives of friends he met in Kentucky.

“Have you heard them say, ‘Life begins at 40’?” Mr. Clarke asked during an early telephone conversation. “Hallelujah. I know it does.”

Life with the Cowboys

Frank Clarke was 26 when he arrived to play for the Cowboys, exposed in the expansion draft by the Cleveland Browns. His coaches at Colorado and Cleveland criticized his blocking, but the Cowboys were still intrigued by the 6-1, 215-pound receiver.

“He was the most attractive guy on a list of old, injured, disposable players,” recalled Gil Brandt, the longtime Cowboys player personnel boss who was charged with putting together the team’s first roster.

It didn’t hurt that Mr. Clarke could blend into new environments. One of only a handful of blacks on the Colorado campus in the mid-1950s, Mr. Clarke was elected the university’s equivalent of homecoming king.

He and John Wooten, the only other black player then on the Colorado team, were segregated from teammates on some road trips. They quietly accepted such indignities, but it wasn’t long before their teammates wouldn’t go to places that didn’t welcome them.

“Frank didn’t have to say anything,” said Gary Nady, a retired Dallas businessman who was Mr. Clarke’s roommate on those trips. “He was the most popular guy on the team. No one wanted to see him and John hurt. It strengthened us as a team.”

In Dallas, Mr. Clarke said he was stunned to find separate public drinking fountains. He was told living in North Dallas was not an option.

Life was different inside the Cowboys’ locker room, where rookie head coach Tom Landry wouldn’t tolerate the slightest sign of bigotry.

“We were concentrating on making the team, not on changing the politics of Dallas County,” Mr. Clarke said. “Tom knew if anyone had an ax to grind because of color, it wasn’t going to work.”

Behind the scenes, Mr. Clarke pushed quietly to improve the plight of minorities around the city. Former City Council member Al Lipscomb, one of Dallas’ most prominent civil rights leaders, recalls Mr. Clarke as “a leader.”

“He didn’t shut his eyes,” said Mr. Wooten, who followed Mr. Clarke to Cleveland and ultimately joined the Cowboys’ front office. “He was a stand-up guy who always pushed for what was right. He would say, ‘This is what we have to do to make it better. Who is going to stand up with me to make it better?’ ”

Instead of picking at Mr. Clarke’s deficiencies, Mr. Landry chose to accentuate his strengths. The coach appreciated Mr. Clarke’s speed, his ability to run precise routes and his soft hands.

Mr. Clarke finished an eight-year Cowboys career with 281 catches for 5,214 yards and 51 touchdowns.

At age 33, he was ready to move on from football. Younger, faster legs had arrived. Bob Hayes had already pushed him to tight end. Mr. Norman shoved him to the bench.

Besides, his future outside the game appeared limitless.

From football to TV

On weekends, Mr. Clarke anchored sports reports for WFAA-TV (Channel 8) when not working NFL games for CBS. During the week, he threw himself into work at a bank and the youth council.

“He had the respect of little toughies and got them back in the main vein,” said Mr. Lipscomb, the ex-council member. “He had the ability to talk to street toughs and CEOs and hold their attention.”

Channel 8 liked the idea of showcasing a former high-profile Cowboy on its air.

“The Cowboys erupted on the scene with the NFL Championship Games against Green Bay in 1966 and 1967,” said Verne Lundquist, Channel 8’s lead sports anchor when Mr. Clarke joined the station in 1968. “The idea was to find the most pleasant, handsome, bright ex-Cowboy and put him on the air.”

But by 1973, Mr. Clarke was ready for another change. Television work at CBS and Channel 8 had lost its allure. There were signs his marriage was coming apart.

“They got married at an early age,” said oldest son Gregory, 55, a Dallas firefighter. “Maybe after my dad left the limelight, he was trying to find himself. Some things were not there. Maybe his marriage was one of them.”

If the Clarke children resented their father for the breakup of their parents’ marriage, they say they have long since re-embraced him. Jeffrey gave up a promising college football career at Washington State to help his mother after the divorce.

“She needed me,” Jeffrey said. “There was no choice.”

Sandra Clarke, 71, lives in the Dallas area. Her children report she isn’t well.

“I can speak for my mother,” said daughter Stephanie, 48, of McKinney. “My mother has always been in love with my father and always will be.”

The move to California offered no professional elixir for Mr. Clarke. He said he felt like a “fish out of water” in the corporate world of construction.

On Feb. 7, 1974, his 40th birthday, he received The Handbook to Higher Consciousness, which lists 12 pathways to “unconditional love and oneness.” Mr. Clarke said the book taught him how to take responsibility for himself and a life structure to find happiness.

“I’ve learned to trust and follow my heart,” he said.

That heart led him to Berkeley and Mr. Keyes’ Living Love Center. Even in a liberal community, the center caused concern. A beat-up old bus always parked out front was considered an eyesore. Inside, rituals included members standing nude in front of the assembly and describing their own bodies.

“At that point, you don’t have to pretend anymore,” said Roedy Green, a Living Love alumnus who is now a Web designer in Victoria, British Columbia. “You’d do the same thing mentally. All the things you had to hide, you came forward with and faced a nonjudgmental crowd.”

Mr. Clarke embraced such concepts.

Even in an accepting community, Mr. Clarke stood out. Carole Thompson, a Living Love leader, said his NFL experiences made him different.

“He was seeing that everyone didn’t live in a competitive, kill-or-be-killed world,” said Ms. Thompson, who dated Mr. Clarke after his divorce and now serves as a minister in San Angelo, Texas.

Commune Cornucopia

In 1977, nearly a decade after his playing days were done, Mr. Clarke faced a decision. With the Living Love Center facing mounting criticism and a desire to expand, Mr. Keyes and his followers purchased the 150-acre Catholic convent in St. Mary, Ky., and established a commune.

The atmosphere in Kentucky was different. Rituals and exercises were less explicit. Families were reared, and children were welcome. But the primary tenet remained the same: the search for personal happiness.

Mr. Clarke was one of the few blacks in the commune, but something else made him noteworthy: He earned a reputation as a gentle giant.

“I think it was a place he got respect. And as a black person, that was hard to do,” said Mr. Green, who also moved to Cornucopia. “Part of it was he was a person who liked helping people. He could calm them. He could help people in emotional turmoil.”

Mr. Clarke reveled most, however, in working with the children. “My calling,” he called it.

“People started having children, and Frank loved being around children and they responded to him. It was just a natural fit,” said Deborah Ham, another Cornucopia alum.

Like all Cornucopia residents, Mr. Clarke’s days were regimented. In addition to assigned tasks called “karma yoga,” there were workshops, group sings and training sessions for visitors.

At first, Cornucopia’s neighbors in St. Mary found the newcomers alien. Commune residents sometimes arrived in town tethered together in an exercise to better understand each other. They frequently would also appear on townspeople’s doorsteps volunteering to help with chores.

“People thought it was a cult at first,” said Susan Spicer, a longtime town resident. “But some of the people were able to kind of insinuate themselves into the community, and quite a few people stayed here.”

Cornucopia dissolved in 1982 because of a power struggle. Mr. Keyes and his followers moved to Coos Bay, Ore. Mr. Clarke followed to take care of Ms. Ham’s twin daughters.

Ms. Ham credits Mr. Clarke for saving the girls’ lives when the brick siding on an incinerator collapsed on them. He heard the commotion and managed to lift the wall.

Later, it took five men to move the wall that Mr. Clarke lifted, Ms. Ham said.

“He’s so present in the moment with the children,” Ms. Ham said. “He laughs and plays with them. It’s a joy to behold. And they love him.”

No car needed

Cherry blossoms line the Duke Park neighborhood that Mr. Clarke now calls home. The trees help shield him from the outside world.

He has no car. Mr. Wooten recalls Mr. Clarke telling him at the 50th reunion of Colorado’s 1956 Orange Bowl team that he didn’t need one.

“I don’t have anywhere to go,” he said, according to Mr. Wooten.

It wasn’t easy finding Mr. Clarke and persuading him to attend the reunion.

“No one believed he’d come,” said Bill Harris, director of the school’s alumni association for athletes. “No one had heard from him in years. People always called asking for him. I had no idea where he was. Finally, I had to put John Wooten on the case, and he convinced him to come.”

Once there, Mr. Clarke gave an impassioned speech, thanking his former teammates for standing up for him and Mr. Wooten.

Those teammates had no idea that when Mr. Clarke moved to Durham, he packed all his possessions in a single suitcase and took a train from Oregon to live with the Tugwells, who are related to a Cornucopia member.

He is in his 27th year as a full-time nanny, living off what he calls a work exchange – caring for children and keeping house for room and board. Even when he returned to his native Wisconsin to care for his elderly mother, he worked as a nanny. When he stayed with son Gregory for several months in the late 1980s, Mr. Clarke served as nanny to his granddaughter.

Reviews of his work have been exemplary. Gal Looft, who says Mr. Clarke worked in her rural Kentucky home for several months, describes his work as “great.”

Reviews of his work have been exemplary. Gal Looft, who says Mr. Clarke worked in her rural Kentucky home for several months, describes his work as “great.”

Ms. Weaver and Mr. Tugwell say they couldn’t be happier with their situation. A month after Mr. Clarke arrived, the parents took infant son Quinn out of day care and entrusted him to the newest member of the household.

“I can’t even tell you how grateful I am,” Ms. Weaver said. “I keep walking around saying to myself that I must’ve done something right at some time to be given this gift.”

Mr. Clarke is involved in community activities and is known to many in the neighborhood as “The Mayor of Duke Park.” Asked whether they know anything about his football background, most neighbors simply shrug.

Mr. Clarke prefers it that way, reiterating that he “lives in the moment.”

Mr. Tugwell said he had no idea of his nanny’s NFL past when he met Mr. Clarke.

“I had to Google Franklin,” said Mr. Tugwell, a longtime Washington Redskins fan. “I said to him, ‘I can’t believe you didn’t tell me about all this.’ ”

Mr. Tugwell has been able to draw some football stories from Mr. Clarke. The men followed intently as Terrell Owens pursued Mr. Clarke’s touchdowns record. After the record fell, Mr. Clarke received an autographed football from Mr. Owens with a message: “Proud to be in the same class as you.”

If Mr. Clarke’s sojourn from the Cotton Bowl to Duke Park doesn’t resonate, he is content to let the world try to figure him out.

All he knows is that he is happy. That’s what he believes really matters.

“You keep doing what you’re doing,” he said. “That’s where I am, knocking on the door of 75, and I’m ready for another 74 years. The rest of my life couldn’t possibly be what the last 74 have been, and I’m ready to go tomorrow, if that’s what the plan is for me.”

July 5, 2008